Crazy Magazine Stunt

(From the Archives – 03.01.02)

As I said in my introduction, the Friday Night News won’t necessarily talk about what’s happening this week at Gale Banks Engineering. We might talk about what’s happening now, what’s in the future, or what happened in the past. Here’s one from a decade and a half ago.

Having been in the automotive magazine business nearly 30 years, I’ve been there and seen a lot. Done a little bit of it myself, too. Considering that our subject matter is high-powered automobiles, and then you throw in some male ego, valor, and testosterone (all part of hot rodding and high-zoot cars, right?), you can imagine that there have been some pretty crazy, zany, and sometimes downright dangerous car magazine stunts. But in many cases they resulted in classic car magazine stories.

More than one of these were the brain children of Terry Cook when he was the editors of Car Craft and Hot Rod. I’d like to think that my “Caddy Hack” article in the January ’87 issue of Hot Rod—when we cut the entire body off a 1970 Cadillac, piece by piece, to show that each reduction in weight made it run the quarter mile quicker—qualifies.

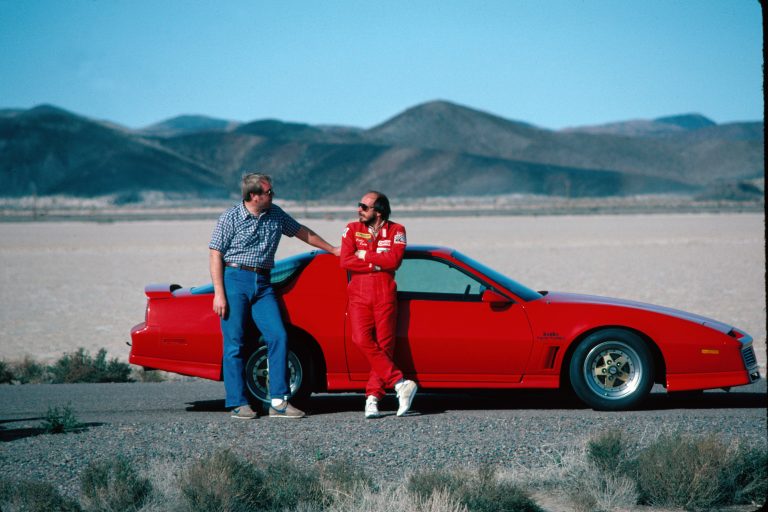

But perhaps the craziest car magazine stunt in recent memory involved a Gale Banks street-driven, twin-turbocharged Pontiac Trans Am, Car and Driver’s then-staff editor Csaba Csere (pronounce the Cs’s like Ch’s; he’s now C&D’s Editor-in-chief), and a string-straight 4.1-mile paved dead-end road known as Mrs. Orcutt’s driveway. Actually, at the time it was Mrs. Orcutt’s driveway.

Here’s the deal. Sometime long ago Mr. And Mrs. Orcutt settled in the Southern California high desert about 25 miles east of Barstow, where they made and sold adobe bricks. Using their own product, they built a nice small home, very much by itself, but only about a mile off old Route 66. But when the U.S. government built I-40 in the ’60s, it ran right between the old highway and the Orcutt’s house. The closest overpass, to get over the freeway, was more than four miles away. So the government’s solution was to build a new, 2-lane, asphalt road from the overpass to the Orcutt’s house. That’s the only place it went. Still does (to its remains, anyway). The best part is that, for most of its length, it was built on a dry lake. So not only is it straight and relatively wide (for a driveway), but it is also very flat. The perfect place to make high speed runs in a street vehicle—crazy high speeds.

It was the early ’80s. “Driver” car mags were full of supercars like Ferrari Testarossas and Boxers, Lamborghini Countachs, BMW M1s and Turbo Porsches–most of them red, and most of them claiming top speeds of 170-180 mph. But Csaba pointed out that, in actual magazine testing, none of these topped 160-164. He wanted to build a real street super coupe that would hit 1-g on the skidpad and top 200 mph. That is, he wanted Gale Banks to build it—and he did.

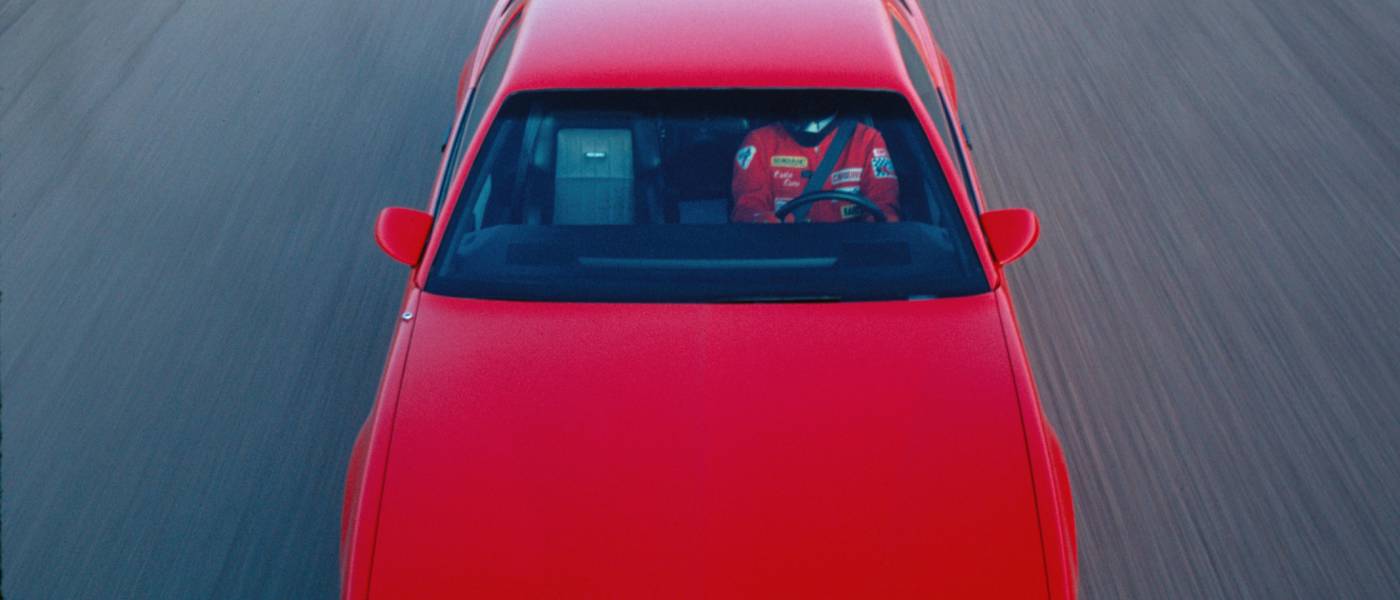

Car and Driver covered the build-up and testing of the car in three issues, primarily Nov. ’83 (skid pad) and June ’84. The car got full suspension and driveline upgrades, went on a diet, and was fitted with a new interior and high-reading gauges. The engine, an all-iron 350 Chevy small-block, was actually pretty mild for such an ambitious project. The major modification was a pair of Banks turbos blowing into an 800-cfm 4-barrel carb. Dynoed at 611 hp, it was fully streetable, right down to a single (large) exhaust and muffler. The one piece of equipment conspicuous by its absence on this car was any kind of roll bar or cage. None of the super coupes had them.

Csaba knew about Mrs. Orcutt’s driveway. The Car & Driver staff had used it more than once to test new cars. Csaba drove the Trans Am to this remote site, along with a support crew including Gale, a photographer, and someone to operate a radar gun to measure speeds. This time they decided to meet Mrs. Orcutt. They reported that she was in her ’70s and “sweet enough to be your grandmother.” They told her they were doing fuel economy testing.

Gale had obviously fully tested the power combination on the dyno. But the run on Mrs. Orcutt’s driveway was the first time that full power was unleashed for a sustained period in the confines of the car. The low frontal area of the Trans Am just didn’t let enough air through to cool the engine under full boost. (Remember that the more power you make, the more heat you create.) This was compounded by the fact that, to keep the car on the 26-foot wide ribbon of asphalt at high speed required all of Csaba’s visual attention. He wasn’t watching the temp gauge. Result: one wounded motor.

Now you’ve got to understand that if the car got off course for any reason (for instance, frying the engine to the point that it might break and dump oil under the rear tires–hey, it happens on real race tracks, but they have guard rails) it would have a hard time keeping the rubber side down. Even where there is level dry lake on either side of the road, it’s about two feet down, it’s covered with plenty of bumps and bushes, and where I walked on it recently, it was about the consistency of oatmeal. Csaba is an excellent, seasoned driver, and he managed to keep the car on course. But numerous changes to the cooling system and air intake did not solve the overheating problem, and Csaba fried another engine.

Finally, Gale completely reworked the water pump (building his own billet impeller) and the air ducting at the front of the car and the back of the hood. Power was no problem, and now the temperature was acceptable. This is when the Highway Patrol showed up, unexpectedly. Fortunately he was more interested in seeing the car run than he was in stopping the program. He and his radio kept any other officers from nosing around. After a 187 mph pass, Csaba decided to go for it, and the radar gun read 196 mph. The Car and Driver guys considered this a success, but Gale wouldn’t settle for anything less than 200-plus. He took the car back to the shop, made a gear change, turned up the turbos a tick, and mounted up a couple different sizes of rear tires.

Back out on Mrs. Orcutt’s driveway once more, the taller tires they hoped to use proved unstable at speed. After swapping to the smaller rear tires, starting near Mrs. Orcutt’s gate and heading west toward the overpass, Csaba nailed it on a banzai pass. For some reason there is no mention of a radar gun reading on this pass, but Csaba watched the tach needle climb to 6100 rpm in high gear—204 mph!

This satisfied everybody, including Gale. But Csaba wasn’t celebrating at that moment. He was sitting in the car near the end of the road, with his windows sealed with racer’s tape (he couldn’t get out), when suddenly “a grizzled elderly lady, brandishing a sawed-off twenty-gauge shotgun, emerges from the desert to express her displeasure with our activities.” Gale vividly remembers arriving at the scene to see this old bag pointing the shotgun directly at Csaba’s window. Perfect ending!

This zany magazine stunt led to a brief Banks spin-off of the ’80s called American Turbocar. Billed, correctly, as the fastest street car ever tested, approximately 20 of these twin-turbo Trans Ams and Camaros were built and sold, including a couple with big blocks. Some are still running on the street today.

Obviously I took a trip up to Mrs. Orcutt’s driveway to see where it is and what it looks like. Mrs. Orcutt is long gone, and her house has been largely vandalized. Her little man-made lake is dry. The road is still straight and empty, but by now there are a few dips in it, and the asphalt seems to be reverting to loose gravel. I’m not saying I would have ever run 200-plus mph on it, myself, but I would seriously question trying to do it today in any sort of low-flying super coupe.

Okay. Was this the craziest car magazine stunt of all time? No way. Not hardly. There’s stuff I can’t even tell you about.

But this was one of the all-time classic car magazine articles.