No smoke with fire

Racecar Engineering April 2008

Smoke free, high efficiency diesel engines are Gale Banks Engineering’s specialty. We look at how the company progressed to become the undisputed leaders in the field.

To understand where native Southern Californian Gale Banks is going, it’s necessary to know where he’s come from. His Gale Banks Engineering company, now in its 50th year of operation, works to extract the most power and efficiency from gas and diesel engines used on land, sea and air, with turbocharging a particular speciality.

When Jet Propulsion Lab and, by extension, California Institute of Technology (Caltech) was granted the funds by Ford Foundation in 1974 to study fuel efficiency, the team asked Banks to join them. ‘They put out a $400,000 grant for the project, asking, “should we have a new engine?” We were to study every engine that existed at that time. No pie in the sky, no paper engines, just real ones,’ Banks recalls.

‘I supplied parts in this evaluation and we ultimately ran a Chevrolet V8 on hydrogen, It was a standard car run on compressed, not liquefied, hydrogen. We took a carburettor intended for a forklift and reconfigured it for use with hydrogen. ‘It worked reasonably well,’ he says. ‘It proved the concept if you will, and was evaluated as a future fuel.

There were hybrids, electrics, all sorts of things – lean burn, stratified charge, all of these based on standard reciprocating auto engines, except for the electrics, obviously, The bottom line is they chose the diesel.’

And so did Banks, who in 1980 was teaching a seminar at the GM Institute on turbocharging engines. ‘It was a graduate level engine design study, specifically engines that were having to be turbocharged. I taught with Hugh Maclnnes, who was an expert on [Corvair] turbocharger design and president of TRW’s turbocharging unit back then.

‘We probed the audience [of almost 500 people] and asked about their specific interests. Over 40 per cent of the people in the audience were interested in diesel, and this floored me,’ Banks laughs, ‘because diesel, other than a heavy truck, didn’t exist in the United States at the time. They were a tenth of a per cent of the automotive population, which is what they still are in the US today.’

As a result of this successful seminar, General Motors asked Banks to turbocharge its then new 6.2-litre diesel engine, destined for its 1982 range of GMC trucks. GM was initially looking for a marine version of the engine and Banks, with intimate experience in marine engineering, took on the project.

SMOKE FREE

His first step was to make the engine smoke free: ‘It smoked without the turbo, but the minute I put the turbo on I could put enough air through the engine to combust all the fuel within the combustion chamber, rather than pump out smoke.’

In the end GM pulled the marine project but asked Banks to prepare a Pontiac Trans Am for land speed runs at Bonneville, with one caveat: he had to use a GMC diesel to transport it So he used the 6.2 -litre GMC turbodiesel.

‘I cleaned up that engine and smoke-free diesel has been my quest ever since. Smoke free, high-efficiency diesel is what we do. Unlike the rest of the performance industry.’

After discussions with Columbus, Indiana-based Cummins Engine Co. Banks branched out into racing diesel-powered trucks, too. Then, at the turn of the century, he went to Cummins headquarters, intending to take part in an afternoon’s discussion about producing a Dodge V8 diesel streamliner for land speed racing. ‘I said to them, well, you know I race a lot at Bonneville, I want to have the first diesel streamliner to go 300mph,’ Banks reminisced.

‘They wanted me to run the company’s new V8, but only three engines existed at the time. I said, “You know, this thing is too young and you don’t have a customer for it yet.” I changed my mind on doing the streamliner while I spoke with them, so said, “why don’t we use one of your engines that goes in a 3/4-ton truck to make the world’s first diesel sport truck?’ The Cummins engineers liked the idea immediately. ‘So we got a used Dakota, used parts that Cummins sent out, including a pre-production common rail engine that had already run on the dyno, and we developed the necessary crankshaft, valve gear, cylinder head and turbocharging system here.’

In order to make the 5.9-litre common rail diesel viable, the Banks engineers had to change the alloy used for the valves, the valve seat themselves, the valve lift, valve springs, valve retainers and pushrods, ‘We went through a number of iterations of camshafts. We also modified the Cummins pistons, along with the connecting rods and camshaft,’ Banks explains.

THE COMBUSTION PROCESS

The racing team at Gale Banks Engineering had a lot of work to do to prepare the cylinder head, which originally had an integral intake manifold. ‘We machined it off to port the cylinder head properly. It was a cast iron intake and was terrible in terms of flow dynamics.’ As a result Banks designed its own manifold, incorporating the stock fuel injection system.

‘We paid real attention to the combustion process and the porting. Because diesels depend on air swirl and swirl torque in the combustion process, we had to be very cognizant of keeping that in place, of keeping that functionality.

The whole point is to maintain the combustion process or you lose engine efficiency and blow smoke.’ And as far as Banks is concerned, that’s the ultimate no-no.

When the team placed its final configuration on the dynamometer, it made 735bhp and the torque was 1350lb. ft. ‘We revved the engine to 3800rpm, which, for that engine, was fast. The original engine turned 2600rpm max, so we were really spinning it hard.’ Eventually though it would end up hitting 5000rpm.

Fitting the new engine into the truck also proved to be somewhat of a challenge as the engine was so long. ‘It almost goes a foot into the passenger compartment: explains Banks, ‘but when we were done, it looked like it was factory. We got our own graphite composite parts, did suspension and chassis work on the truck, and the only stock parts were body panels. We also lowered the truck considerably, but it was still completely street driveable.’

LAND SPEED RACING

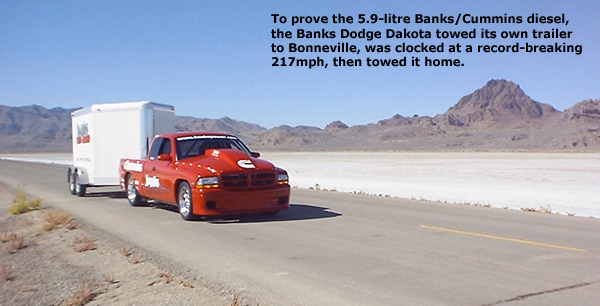

By 2002, the red Dodge Dakota Sidewinder was ready for action at the Bonneville salt flats. To further emphasise its credentials, as it is capable of pulling a 5000 lb. trailer, Banks made sure the truck did just that, using it to tow its own racing gear to Bonneville, where the crew set about changing to the appropriate racing wheels and tyres and set it up with the right ratios with quick-change gearing.

‘I took a small engine and made a big engine out of it,’ says Banks. ‘This thing can not only tow its own support trailer, it can tow a Ferrari Enzo on its trailer to Bonneville, unload the Ferrari, beat it and bring it back home to Los Angeles. The Enzo cannot return the favour. And the fuel efficiency? We’ve got three times the efficiency of an Enzo!’

With driver Don Alexander aboard, on the five-mile course at Bonneville the world’s first diesel sport truck performed exactly as the Banks team hoped, setting a one-way speed of 222mph and a two way, FIA-registered average of 217 mph, which still stands as a class record today. However, never content to just sit back, the Banks team intend to beat its own record: ‘We’re going to run the truck one more time this year and see if we can push it higher!’

Although Banks didn’t measure fuel efficiency on that 2002 trip to Utah and back, he did take part in the 2003 Hot Rod magazine 1,600-mile trip starting in Wisconsin and ending in Florida. ‘On the highway, we were not running normal highway speeds but we still ran right at 24mpg. There were sections when we might be running at 140, but had the potential to go higher. So we achieved high speed fuel economy, though not at normal freeway speeds.’

ROAD RACING

Safe in the knowledge that he had the world’s fastest diesel pick-up truck, Banks decided to go road racing with a diesel pick-up. He took the GMC Sierra 6.6-litre Duramax V8, that’s been GM’s diesel engine of record and prepared it for endurance contests of three to 25 hours. ‘We’ve been to (local race tracks) Buttonwillow, Willow Springs and Thunderhill many times but I don’t just want to run it, I want to finish with it.’

First time out with the Type R Duramax diesel, Banks entered the 3900lb., rear-wheel drive truck in a NASA three-hour enduro race at Buttonwillow in March 2006. ‘We practiced, and there were 167 cars there, but only three of them ran under two-minute laps in practice. The fastest was a 1:57 for an SRT10 Viper prepared by Roush, an [open wheel] car ran 1:58 and we ran 1:59 the first time out,’ he says proudly.

‘We practiced for about three hours, entered the enduro, started the race and, on the very first lap, sheared off the engine input shaft at the rear axle. Talk about timing! At least we started the race, but we found out we had a three-hour rear axle. Then we discovered we had a three-hour transmission…’

While he awaits action on that front from Costa Mesa, California-based Traction Products (who are deriving the right electronics for a paddle shift transmission for the road racer), Banks has other projects in the mix.

DRAG RACING

‘The latest thing we’re doing with the Duramax diesel is this: we’re going drag racing,’ explains Banks, based on his understanding of the American racing culture.

‘If you want to talk about road racing in the United States, most people know nothing about road racing, It’s huge in Europe and the UK, but it’s not an ‘everyman’ type of sport. But NHRA is and NASCAR is, so we looked at associations with either.’

It soon became obvious to Banks though that NASCAR simply wasn’t ready for diesel. ‘Maybe one day they might have a diesel truck class,’ he says, but right now he doesn’t seem positive about it. In particular, he is disturbed by both NASCAR and NHRA’s continued use of carburetted V8 engines, as it just appears backward to him.

‘You don’t see electronic fuel injection in NHRA. Even in the nitro classes they use mechanical fuel injection as electronic is banned. So is turbocharging, and I have a bigger history with turbocharging than I do with diesel,’ Banks reminds us. ‘All of my records are with turbocharged engines.’

The NHRA’s rules on turbocharging in its top, nitro-based classes stopped Banks from working in those arenas, but he could and does have the ability to race a turbocharged, nitrous-consuming diesel engine in NHRA competition.

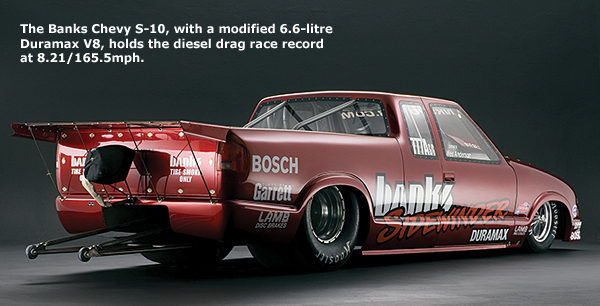

So, beginning in late 2005 and using the information, experience and machinery from the road racing engine, Banks constructed a Sidewinder Duramax S-10 pick-up and took it to Las Vegas in October 2007 for its first competitive outing at the NHRA’s ACDelco Nationals.

RECORD EFFORT

Up against a truck that came from Texas specifically to defeat Banks, the Californian had his day. After a single test outing close to home a week earlier, Banks’ S-10 ran four times on the Las Vegas quarter mile, establishing a record effort at 8.21 seconds with a terminal speed of 165.50mph. Unsurprisingly, each pass occurred without the acrid, black diesel smoke that typified the other diesel’s runs.

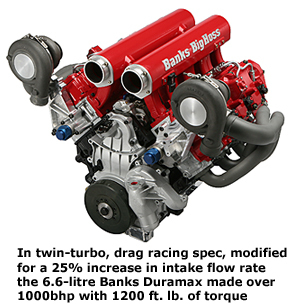

To get the output needed, Banks modified the 6.6-litre Duramax engine out of the road-racing Sierra pick-up as time constraints didn’t allow for the build-up of a specific drag racing engine. This, incidentally, was still unfinished at press time. The block was modified to accommodate a multi-stage, dry sump oiling system and fitted with a special billet oil pan and block reinforcement girdle, all of which were fabricated in house.

The stock crankshaft was carefully cleaned and checked, then fitted with Crower I-beam connecting rods that use CoBer tool steel wrist pins. The reciprocating package includes Mahle 16.5:1 forged racing pistons, a Banks-spec roller camshaft and lifters and a Banks custom built front counterweight and harmonic balancer.

Using a Banks Big Hoss intake cylinder head, designed to keep a high intake swirl, thereby ensuring effective combustion in the engine. The Banks team also installed smaller, lighter and shorter roller lifters, LSM bronze lifter guide sleeves and 34mm stainless steel valves, which use custom valve springs, retainers and keepers.

With twin Honeywell/Garrett 12 lb. TR30R racing turbochargers with custom stainless exhausts, Banks-spec wastegates and a Banks-spec nitrous system. The package delivers upwards of 1000bhp and over 1200lb. ft of torque with a single CP3.3 fuel pump calibrated to 1800bar pressure. The S-10 uses eight high-performance CRIN2 Bosch fuel injectors, regulated by Bosch’s DC-16 ECU.

To transmit the power Banks uses one of his own billet torque converters mated to a Liberty five-speed transmission, along with a Mark Williams’ high-torque axle, centre section and gears.

At the time of writing, the Sidewinder Duramax S-10 drag truck was due to make its second professional appearance at NHRA’s early February season opener at Auto Club Raceway in Pomona, Los Angeles.

To prepare for this, the Banks team set out for a practice and test session in mid-December. Still in road-race engine configuration, they took the S-10 to the NHRA-sanctioned Speedworld drag strip in Wittmann, Arizona, where it stopped the clocks quicker and faster than when it set the new record in Las Vegas.

The truck ran 7.96 seconds at 167.34mph, making it the first diesel in the world into the sevens. Admittedly, these figures aren’t official, but they give an idea of how far Banks is progressing with an engine initially prepared for road racing. [update: the Banks S-10 has now run 7.77/180 mph]

Looking further forward, Banks says he is returning to Bonneville this year with his Sidewinder, as well as hoping to make the road racing Type R Duramax feasible for a 25-hour race, and is looking to break all diesel drag race records with the Sidewinder Duramax S-10. ‘We currently have the world’s fastest diesel pick-up, we have the world’s quickest and fastest diesel drag truck and we have the first road racing diesel pick-up,’ he states, but it’s clear he feels there is more to come.

XPRIZE PROJECT

Meanwhile, Banks is heavily involved with the $25 million XPrize project, helping establish rules for a contest to develop a car that can go coast to coast across the United States and achieve 100mpg. ‘These would be commercial, street-driven vehicles, prototype vehicles, getting a minimum of 100mpg, passing emissions, passing safety regulations, all of it,’ he explains. ‘And it must be attractive, do 0-60 in about 1 2 seconds and have a skidpad number around .75. It’s got to be a real car!’ he notes with glee.

Currently, he is just over a year and a half into this project which already has some aerospace industry input. ‘We’re encouraging people to come up with ideas for the automotive industry,’ he said. And if that sounds like a full circle for Gale Banks, well, it is.

About Gale Banks: Born in California during the Second World War, Banks recognised early on that he was destined to be part of the hot rod culture that was emerging around him. He embraced the environment and, with a mechanical aptitude and a penchant for the scientific, began building fast cars that had enviable efficiency. The combination has been Banks’ mantra ever since.

Born in California during the Second World War, Banks recognised early on that he was destined to be part of the hot rod culture that was emerging around him. He embraced the environment and, with a mechanical aptitude and a penchant for the scientific, began building fast cars that had enviable efficiency. The combination has been Banks’ mantra ever since.

Starting on the streets, Banks moved up the competition ladder with his homebuilt machines, beating drivers who often had more money and machinery. What drove him was his hunger to learn why and how machinery reacted to his input.

Lacking the funding to secure schooling at Caltech (California Institute of Technology), he attended Cal Poly and graduated with an engineering degree and a reputation for his ability to find an engine’s sweet spot.

After college, he relocated Gale Banks Race Engines to San Gabriel, CA, close to Caltech and Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL), institutions where he made many friends.

Gale Banks Engineering currently encompasses six buildings in Azusa, CA, and has around 200 employees. It continues to specialize in gaining power and efficiency for anything motorized.