The Banks Engine Test Cells – State of the Art and Ever-Changing

There are a number of areas located throughout the 11+ acre Banks design and manufacturing facility that are dedicated specifically to testing. This Friday we’re specifically looking at the engine test cells.

The way that Gale Banks sees it, THE most important part of the business that he’s been in for just over half a century now is testing. Cool new products can look just wonderful on paper, be absolutely stunning as mock-ups, and even show unlimited potential in the virtual world of computer simulations.

But NONE OF THE ABOVE is how any product is ever judged at Banks Power.

No, every component, every assembly, every piece of high performance equipment that Banks makes (along with many of our competitors’ products) is constantly subjected to what amounts to brutal physical testing, testing that benchmarks performance and assures durability.

There are a number of areas located throughout the 11+ acre Banks design and manufacturing facility that are dedicated specifically to testing. This Friday we’re specifically looking at the engine test cells. But there are also test benches for electronics and computer-controlled airflow stations through which all new designs must pass successfully before being put into the extensive Banks Power product catalog.

There is also a large (and constantly growing!) test fleet of vehicles where “real-world” means exactly that and where fully-instrumented long drives under heavy loads are the order of the day – – every day – – day in and day out.

Holding every new Banks products’ feet to the fire is a huge internal operation. A quick look through the thick Banks catalog or a click through the website will reveal some of the over 1,200 different products, pieces, and complete kits that all needed to be thoroughly tested before sending them off to work in the outside world.

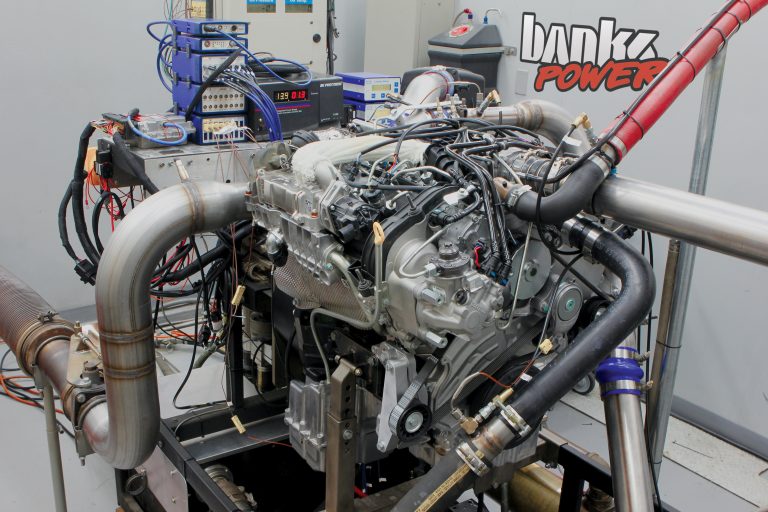

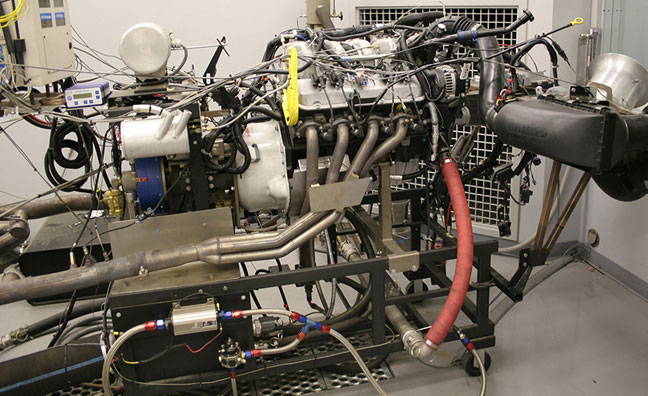

Banks’ twin engine test bays are always a highlight of any shop tour. Of all the sights: work benches stacked with projects, tool boxes, large scale shop machinery, even the sleek race cars themselves …it’s the dynos (especially if they’re in operation) that attract both the eyes and the ears with a chance to see (and hear) something that’s usually buried under a hood, and normally muffled by metal on all sides.

There is a constant upgrading of instrumentation in the Banks test cells and that work revolves around responding to the number of ever-changing and ever-toughening test regimens. Widely differing standards are required by different organizations. Each test “protocol” relating to what those specific entities want to see tested, for how long, and how hard.

Right now, a number of the projects here at Banks are being tested using what’s known as the “NATO Cycle” – an extreme duty set of runs that last as long as 400 hours (that’s 16 ½ days) of continuous full-throttle loading and unloading in 40 ten-hour sessions on the Banks engine dyno!

These merciless runs will be completely computer-controlled as the engine speeds right up to red line – – hold, hold, hold, drop throttle, count to two, do that again, and again, and then over again for six hours straight. Idle to full throttle under full load, now half load, now half-throttle with a full load, back to idle, back to wide open with no load, and then full-out, pegged, right on the governor for two hours …and so on. Thousands of lines of code, a stream of 0’s and 1’s all processing marching orders at the speed of light, and all trying hard to do great bodily harm to that engine up on the test stand.

As anyone who works at Banks will tell you, Mister Banks has a full set of industry-leading standards when it comes to any testing and test data at the place with his name out front. There will be many long hours spent making sure that the Banks test equipment is dialed-in perfectly before any (the NATO regs. specify a maximum 2% working tolerance across the board) of the new series of runs is made.

The precise controls on throttle and load, combines with 60-plus data points streaming in off the engine, telling the control room every secret from inside and outside of this engine as it runs. This is about as close to sending the screaming engine through a giant metal X-Ray or MRI machine as you can get… No detail of its status is a secret to the operators. It’s all there up on the twin flat screen monitors in blazing color.

Today the goal is fashioning the test regimen to replicate actual extreme service load and speed conditions as close as possible. Dyno testing is different from testing on paper, or in a computer simulation, where only theory is being tried out, because the engine really runs. On the other hand, it runs in a very-carefully controlled environment, fastened to a stand, festooned with wires and sensors, with a number of people watching it trough an inch-thick sheet of ballistic glass that’s guaranteed to stop a round from a .45 delivered at point-blank range. This makes an engine dyno sort of a “hybrid” test method. Not quite “real world”, but real in its own circumstances and often paced far harder than any situation that would be seen there.

In action (real life) these engines must be able to (quietly) idle for hours and hours on end but respond instantly to a call to duty which requires full throttle for who knows how long. These are gritty tests, grueling, nasty, marathon dyno tests that make every “engine person” at Banks almost wince when they walk by the test bay. On the other hand, we can tell you that these engines are destined for some highly important “government” work, so the super-tough workout is considered a “good thing” here.

One last component of all this research and testing, easily the most complex and by far the most important: are the people who operate the equipment.

At Banks there are people for whom getting the information and getting it right is more than just a job. They understand that the information that they develop is every bit as important as the initial design itself, they want every Banks design to be THE best there is, and they take pride in their part of the process, it’s part of every project.