A Gathering of Land-Speed Luminaries

Record holders and car builders convened recently in Pomona, Calif., to discuss the preparation, promotion and psychology of chasing a land-speed record.

From the February 20, 2012 edition of The New York Times:

Away From the Salt Flats, a Gathering of Land-Speed Luminaries

By RONALD AHRENS

POMONA, Calif. – For all the wind-tunnel testing and manic fund-raising that may precede an effort to set a land-speed record on the Bonneville Salt Flats, success ultimately depends on the performance of that most volatile variable, the driver.

This consensus emerged last Saturday, when record-setting drivers and car builders gathered at the Wally Parks N.H.R.A. Motorsports Museum for a panel discussion about the preparation, promotion and psychology of chasing a land-speed record. The discussion preceded an awards banquet for the local Sidewinders car club.

The panel discussion also emphasized how interest in the sport was being renewed by young teams with new technologies. If only, the panelists lamented, the same could be said for the salt on which they raced. The thick coating at the Bonneville Salt Flats, the 46-square-mile prehistoric lake bed in northwestern Utah, has eroded, the racers noted, echoing sentiments from preservation campaigns, notably Save the Salt. Among the panelists was Ron Main, co-owner of Speed Demon, a piston-powered, wheel-driven streamliner. Speed Demon, piloted by Mr. Main’s racing partner George Poteet, was powered by a twin-turbocharged Chevrolet V-8 making 2,077 horsepower. Ken Duttweiler, who built the powertrain, also joined the panel. Through their combined efforts, Speed Demon hit 462 miles per hour last fall, a record for the blown-fuel category. The only streamliners that have moved more quickly have been propelled by the unabated thrust of turbine engines.

The panel discussion also emphasized how interest in the sport was being renewed by young teams with new technologies. If only, the panelists lamented, the same could be said for the salt on which they raced. The thick coating at the Bonneville Salt Flats, the 46-square-mile prehistoric lake bed in northwestern Utah, has eroded, the racers noted, echoing sentiments from preservation campaigns, notably Save the Salt. Among the panelists was Ron Main, co-owner of Speed Demon, a piston-powered, wheel-driven streamliner. Speed Demon, piloted by Mr. Main’s racing partner George Poteet, was powered by a twin-turbocharged Chevrolet V-8 making 2,077 horsepower. Ken Duttweiler, who built the powertrain, also joined the panel. Through their combined efforts, Speed Demon hit 462 miles per hour last fall, a record for the blown-fuel category. The only streamliners that have moved more quickly have been propelled by the unabated thrust of turbine engines.

Gale Banks, president of Gale Banks Engineering of Azusa, Calif., who started building and selling engines more than 50 years ago as a high school student, led the discussion. “I’m a gearhead,” he said to open the meeting. “I cannot get over it, and there’s no 12-step program for me.”

Mr. Banks asked the similarly afflicted panelists about their strategies for maintaining traction on the hard and sometimes slick salt. He said he vividly recalled walking the course after a day’s racing, following a trail of rubber that was interrupted only by obvious gear changes, when the drive wheels stopped spinning.

“Wheel slip is kind of a big deal,” he said.

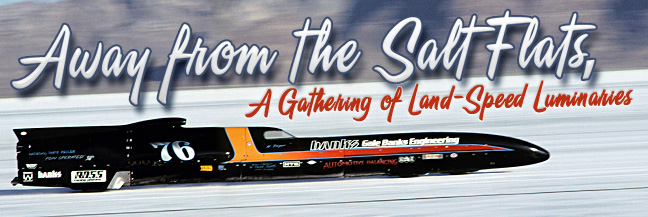

Panelist Al Teague, whose Spirit of ’76 streamliner set a record in 1991, said he allowed for a small factor of wheel slip because of the importance of “driver feel.” Mr. Teague and others used to run on shaved Firestone tires discarded after Indy series races, which they would pump as high as 150 p.s.i. An alarmingly frayed example from one Bonneville sortie was on display during the discussion.

Panelist Al Teague, whose Spirit of ’76 streamliner set a record in 1991, said he allowed for a small factor of wheel slip because of the importance of “driver feel.” Mr. Teague and others used to run on shaved Firestone tires discarded after Indy series races, which they would pump as high as 150 p.s.i. An alarmingly frayed example from one Bonneville sortie was on display during the discussion.

Vehicle suspension strategies were another issue. Generally, according to panelists, the flexible sidewalls of pneumatic tires were preferred over the solid disc wheels used on the Thrust SSC land jet that set the absolute land-speed record of 763 m.p.h in 1997. Mr. Teague said the sidewall, even with 100 pounds of pressure, could be used for initial suspension. Mr. Duttweiler, meanwhile, said a “semisolid,” or partially sprung, front end served nicely on Speed Demon. Too much suspension, however, could lead to uncontrollable oscillations.

To read the rest of the story, visit The New York Times website »

Check out the Teague-Welch-Banks Streamliner in action!

Visit the NHRA Museum website »

See all the stories from the Wally Parks NHRA Motorsports Museum

here »