Mastering Teamwork at the Baja 1000

Four Wheeler May 2005

Banks Power teams up with Kent Kroeker and his KORE racing Dodge Ram.

It was 2 a.m. and we were closing fast on the remote village of El Arco, still over 100 miles from our second pit. We’d been strapped in our seats for over 13 hours. The dust plume from the buggy in front of us reduced our visibility to almost zero. Kent Kroeker was silent, hands on the wheel, leaning forward slightly, often toggling between the HIDs and the truck’s factory lighting. As our truck crested each hill, our lights would reveal a small proton of merciless trail, the only reassurance that we were on track and still in the race. Kroeker said, “Good, we’ve got him.” Shortly thereafter, he announced ecstatically, “I love this.”

It was that very moment when I realized our teamwork was completely responsible for our fate. One wrong move here and we could all be dead. The reality of the situation left no room for error. I turned to Kroeker and for the briefest of moments felt fearful of what lay ahead. The distinctive sound of our turbodiesel engine pierced the night silence as few had ever before. The sound was purposeful, continuous and voracious, like a freight train at full tilt, screaming across the landscape. “We’re showing 36 pounds of boost and 3,100 rpm,” I replied. “This is where this truck exceeds over all other vehicles,” Kroeker assured me.

The GPS read 97 mph. “Hard right turn in less than a mile,” I yelled, teeth clenched, focused on the moving map display.

“How hard?” Kroeker asked, trying to sound calm.

“Looks like 80 degrees, then into a sweeping left–decreasing radius … be careful!” I replied.

As we entered the turn, Kroeker didn’t touch the brakes. Wheels, tires, tube frame, and engine materialized out of the dust. Our rate of closure was too fast–we were about to hit the other vehicle! Kroeker applied the brakes violently, pitching us sideways, aligning the race car and its dust to our right. As we rounded the corner, the winds shifted to the opposite side and we could see ahead for the first time in 80 miles. Kroeker got back on the throttle. With a sigh of relief, and almost an hour of battle, we’d finally passed the buggy. Ahead in the distance we could see another plume of dust. It was on again.

Baja Honor Code

Baja Honor Code

This was a scene from the 37th annual trans-peninsular Baja 1000, the longest continuous off-road race in the world. This year, I had the opportunity to co-drive the entire race with Kent Kroeker, president of Kroeker Off Road Engineering (KORE), a company that specializes in aftermarket Dodge Ram 4×4 suspensions. We were to compete in KORE’s project vehicle, a black ’03 Dodge Ram 2500 4×4 known affectionately as “The Beast.”

The Beast has some mandatory safety equipment installed, some upgrades and reinforcements to make it competitive, but it’s essentially a stock truck that you can purchase at your local Dodge dealer.

When I’d asked Kent what it was going to be like to race a 9,500-pound diesel truck for more than 1,000 miles off-pavement, day into night into day into night again, he just looked at me sideways and, in a low voice, said one word.

“Heinous.”

He wasn’t kidding, either. We drove continuously for 29 hours, 23 minutes, and 10 seconds. It was a punishing, brutal experience, a challenging exercise in teamwork – and one of the greatest adventures I’ve ever experienced. We ended up taking Third in the SCORE Stock Full class. We even finished in front of Robby Gordon’s Trophy Truck.

What made our effort so significant was the fact that this was the first Cummins turbodiesel-powered vehicle ever to finish the Baja 1000.

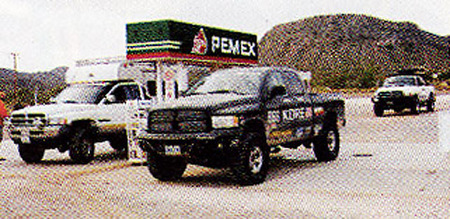

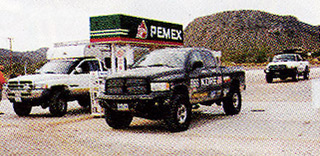

You may ask, “Why race a diesel-powered truck in the Baja 1000?” How about 12.7 mpg at full race speed? The average trophy truck makes about 700 hp, but also consumes between 750 and 1,000 gallons of special, high-octane race fuel. This means a Trophy Truck has to stop 10 to 12 times during each race for fuel. Every time you stop, your speed average goes to zero. The KORE race truck only had to stop for fuel three times. And we used Mexican pump diesel the whole way.

At one point during the race, we stopped to help a team in a badly stuck Class 7 two-wheel-drive Toyota. Unfortunately, many Baja race vehicles are two-wheel drives, so when they encounter deep mud or silt beds, they often get trapped. These guys were helplessly mired in deep Baja muck, and had no hope of escape until we pulled up. We wanted to keep our average speed high, but knew at the same time we had the perfect vehicle to resolve the situation. It was a treacherous area where both the trail and a river squeezed through a narrow canyon. Vegetation in this area was thick, and each side of the trail seemed to suspend any hope of a detour. To make matters worse, six additional vehicles were trapped behind the Toyota. Each rig had an unhappy co-driver working strenuously to free the vehicle from the muck. Each guy was covered from head to toe in black mud from the canyon floor. I quickly assessed the situation, realizing time was of the essence. With the snap of a strap, out came the marooned truck. Grateful drivers cheered us on sincerely as we reversed and then gave the Toyota a final pull to freedom. After a quick handshake, I leapt back in my seat. As I buckled my harness, I looked down at the GPS unit, astonished to see our act of sportsmanship had only cost us 12 minutes. As we drove off into the night, we heard one driver comment to SCORE race officials on the Weatherman frequency, “We just got pulled out by the gnarliest Dodge Ram in the world!” We felt like heroes–and indeed we were to the dozen or so guys who were now back in the running.

Rolling the Dice

So what does it take to tackle the Baja 1000?

Basically, you figure out what might go wrong and build your machine to overcome potential problems.

Essentially, the liabilities can be summarized as: hideous terrain, purpose-built booby traps, absolute darkness at night, severe dust, dense fog, and distance with high speeds.

Let’s not forget isolation, testosterone, adrenaline, clueless spectators, mindless livestock, and scarce medical facilities. Mix it all up in a Third World country and you’ve got the most dangerous race in the world–the Baja 1000.

Let’s not forget isolation, testosterone, adrenaline, clueless spectators, mindless livestock, and scarce medical facilities. Mix it all up in a Third World country and you’ve got the most dangerous race in the world–the Baja 1000.

To combat these problems and to ensure our race effort wasn’t wasted, we had a rollcage, five-point harnesses, a fuel cell, HID lighting, VHF radio, a GPS unit–and last but not least, an effective team of experienced crew members. Quick thinkers and mechanical-minded individuals can always improve your chances of victory.

One more thing–the final uncontrollable factor: luck. You can have all the money and experience in the world, but if you’re out of luck during the race period, you’re wasting your time.

“We just got pulled out by the gnarliest Dodge Ram in the world!”

In San Ignacio, during our second pit, I was relieved of navigation duties by pro Baja racer, and former Navy SEAL, Rod Hamby. By this point I had been awake for almost 20 hours. For 14 hours I had served as navigator and radio operator, risking my life as we passed cars in the darkness, skirting 200-foot cliffs dropping to the Sea of Cortez. After 550 miles of intense mental concentration and punishing physical abuse, I was hungry, dehydrated, and worn out. As Hamby took the right seat, Kroeker asked if I wanted to continue on in the center rear seat, to operate the radio and help clear turns. “You bet!” I said, “This is the Baja 1000! I don’t care how bad it hurts!” Kroeker said, “OK, now it’s official–you’re gnarly! Get in!”

In San Ignacio, during our second pit, I was relieved of navigation duties by pro Baja racer, and former Navy SEAL, Rod Hamby. By this point I had been awake for almost 20 hours. For 14 hours I had served as navigator and radio operator, risking my life as we passed cars in the darkness, skirting 200-foot cliffs dropping to the Sea of Cortez. After 550 miles of intense mental concentration and punishing physical abuse, I was hungry, dehydrated, and worn out. As Hamby took the right seat, Kroeker asked if I wanted to continue on in the center rear seat, to operate the radio and help clear turns. “You bet!” I said, “This is the Baja 1000! I don’t care how bad it hurts!” Kroeker said, “OK, now it’s official–you’re gnarly! Get in!”

Leaving San Ignacio, I was impressed by the calm, almost nonchalant tone that Kroeker and Hamby established in the cockpit. While passing race cars in the dust at breakneck speeds they talked to each other as if they were having coffee at Starbuck’s–just another day in the office for them. I started calling Hamby “The Human GPS” because he knew more shortcuts, course subtleties, and terrain features than were found on the moving map display.

About an hour before sunrise, under full throttle down a dark, lonely road, Kroeker suddenly pitched the truck sideways, rolled up over an embankment, then got us back on course, narrowly missing a yard-deep ditch that the locals had dug across the course. “That would have been a bad finish for us,” Kroeker said, “The entire axle would have been torn off–hero to zero in one second.”

By the time we had arrived at pit 3 in Insurgentes, we were well established in Second place, running strong behind Chad Hall in his factory-sponsored H1 Hummer. He was only 20 minutes ahead of us, and we were gaining fast.

That’s when the whoops got really deep. Unfortunately, our efforts to preserve our truck were no match for Hall’s high-dollar H1.

50 Miles from Glory

Essentially, all of Baja is comprised of whoops. They call small, continuous whoops “washboard” and the really big ones “rollers” because they’re so big you have to roll over them one at a time. For the next three hours, we were in the rollers–the deepest, sandiest whoops I had ever seen. It was almost as if symbolically the Baja had saved the best for last. It was an affliction like no other.

Finally out of the rollers, the sun setting behind us, and the finish looming less than 50 miles away, we felt certain we would take Second place. Kroeker kept asking me to look back for Bob Graham’s Nissan Titan–a vehicle we had been dicing with earlier. I kept saying he was nowhere in sight, but Kroeker knew better. Suddenly, out of nowhere, the Titan appeared. I suggested trying to get it stuck in the deepest silt beds we could find. We knew we had some advantages over the lower, less-powerful Titan. This worked for a while – Graham would slow momentarily but would always catch up. Then he rammed us hard in the right rear quarter panel. Baja racers call this “nerfing.” It’s a communication technique that says, “You better let me pass because I’ve been driving for almost 30 hours and I’m finally out of my mind!” Not wanting to hinder our chances of simply finishing, we let him pass, hoping that as he pushed his truck to its limits, he might break something.

“You better let me pass because I’ve been driving for almost 30 hours and I’m finally out of my mind!”

Minutes later, we could see the lights of La Paz shining off in the distance. It was a beautiful sight. I had no idea it would encompass such feelings of accomplishment. As we rolled across the finish line, I finally understood the mystique that captivates so many racers in Baja. Passing under that Tecate banner, I gained the knowledge that only comes from experiencing it firsthand. We’d survived the toughest vehicular evaluation known to man. At the finish, we congratulated each other and laughed with Graham about the nerfing incident. Kroeker even jokingly demanded to see his insurance papers.

Minutes later, we could see the lights of La Paz shining off in the distance. It was a beautiful sight. I had no idea it would encompass such feelings of accomplishment. As we rolled across the finish line, I finally understood the mystique that captivates so many racers in Baja. Passing under that Tecate banner, I gained the knowledge that only comes from experiencing it firsthand. We’d survived the toughest vehicular evaluation known to man. At the finish, we congratulated each other and laughed with Graham about the nerfing incident. Kroeker even jokingly demanded to see his insurance papers.

Perhaps the greatest element of this story is what followed the race. Contrary to traditional post-1000 regimen, while other racers were loading their vehicles onto trailers or into semi-trucks for the 1,000-mile return trip, we simply fired up The Beast, turned on the air conditioning, put in a CD, and drove back to California.

Perhaps the greatest element of this story is what followed the race. Contrary to traditional post-1000 regimen, while other racers were loading their vehicles onto trailers or into semi-trucks for the 1,000-mile return trip, we simply fired up The Beast, turned on the air conditioning, put in a CD, and drove back to California.

Special Thanks

Kroeker Off Road Engineering LLC

760/749-8687, www.koreperformance.com