Holy Smokeless!

Mopar Now Spring 2003

Here’s one for the run-whatcha-brung record books. And we do mean record books. Last October 17, with the Bonneville Nationals World Finals already well underway at Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats, the crew from Gale Banks Engineering pulled in after driving all night from their headquarters in Azusa, Calif. They unhitched the trailer from their Dodge Dakota tow vehicle and on Saturday set the world speed record for pickup trucks – with the tow vehicle!

This was no ordinary tow vehicle. Banks calls this Dakota project Sidewinder, the result of a goal to build a fully streetable sport truck that can kick butt in any arena – Bonneville, the drag strip, a road course, the street, mud wrestling – you name it. All with a fuel no ordinary Dakota can burn today – diesel. That may change, as Chrysler is hitching its power wagon to oil-burning SUVs and light trucks (see page 8, Spontaneous Combustion” in this issue)

Banks is no stranger to the salt flats. The record he was aiming to break with the Dakota was one he had set with a GMC Syclone at 204 mph. Banks has also set records for the world’s fastest piston-engine automobile and world’s fastest passenger car. We’d be interested to see him make the world’s fastest waffle iron.

Banks is also a huge diesel advocate and pickup truck and RV owners have been turning to him for years for his power-boosting kits – for gas engines, too. With the latest technology, Banks figured an oil burner ought to be able to smoke that Syclone right out of the history books. He was correct. The Sidewinder now holds the world record for pickups at 217.314 mph. It had gone faster, hitting 222.139 mph on one qualifying run. Just shows what you can do with 1,300 lb. –ft of torque in a 5,000-plus pound truck – and with nary a smoky trail against the blindingly white salt surface.

Banks started with a stock Cummins 5.9 turbodiesel blueprinted by Cummins engineers on their own time. Dubbed the “Salt Quake” engine, it used bonestock 2003 components except for a warmed-over ECM programmed to deliver more fuel. In this baseline form, the Salt Quake was already quaking out a truly impressive 393 horsepower at 3,800 rpm and 600 lb.-ft. of torque over a “broad rpm range.” The electronics are Cummins and the fuel injection is state-of-the-art common rail. “It is deceptively quiet and doesn’t sound like it’s laboring even when subjected to a full load on the dyno,” says Banks. Funny, we’d say the same about our editor.

Then the Banks crew went to work. Like it’s gasoline cousin, a diesel engine is a big air pump. So performance gains started making it pump more air, starting with Bank’s own porting and polishing job on the head. After that came a new camshaft, their own intake and exhaust manifolds and a Holset variable-geometry HY55 turbo. The oiling system remains stock except for modifications to the pan for extra ground clearance and capacity. By the time they were done, there was an astounding 735 horsepower and 1,300 lb.-ft. of torque coming out of this monster.

The variable geometry turbo allows rapid changes in boost pressure, as dictated by the banks Engineering electronics. Many Mopurists know all about variable geometry and not from high school. Chrysler was the first car maker to offer a variable nozzle turbo (VNT) in production cars in the late 1980’s, although production was scarce.

This was no easy engine swap. Fitting the long tall Cummins to the Dak required extensive firewall and floor surgery. You might ask, why not just drop the big diesel into the lightest Ram, which should accept the Cummins no problem? In a word, aerodynamics. One look at the Rock of Gibraltar prow on the new Ram tells you it’s not the ideal starting point for a salt runner. When it comes to parting the air at 200-plus mph, less is certainly more.

Chassis dyno testing and coastdown testing revealed that the Dak would need more than 800 horsepower to reach 210 mph with it’s stock aerodynamics. But by lowering the truck to race configuration and cleaning up the aero profile with a front air dam and other allowed modifications, the horsepower requirement fell to about 600. So going in with 735 ponies, Banks was pretty sure of the outcome at Bonneville.

The common rail fuel injection operates under extremely high fuel pressure, and electronically controlled solenoids inject fuel directly into each cylinder – also controlled by Banks Engineering’s electronics. The No. 2 diesel fuel flows from a 22-gallon fuel cell through 5/8-inch lines to an adjacent Holley 110 GPM pump, which supplements the stock Cummins diesel lift pump in the engine compartment. The fuel then flows through a stock Cummins fuel filter/water separator assembly and then to the mechanical high-pressure fuel pump.

For the Bonneville effort, the twin Cummins marine air-to-water intercoolers are fed by dual Stewart – E.M.P. high-capacity electric water pumps. The combined water flow rate is 120 gallons per minute. Intercooling for the street is less complex, because Sidewinder doesn’t need to run the 52 psi of boost (yeah, 52!) that it did for the speed trials. In street guise, the Sidewinder uses a Banks Techni-Cooler air-to-air intercooler installed in front of the radiator, which keeps intake air temperatures to less than 150º F.

The Banks VGT controller regulates the turbo’s variable geometry and turbo shaft speed according to varying input from the driver, engine and road conditions. The technology allows torque curve shaping not even imagined in the past.

In keeping with the “sport truck” mission, the Banks crew insisted on a manual tranny for the Sidewinder. It’s the New Venture Gear six-speed that’s used in V-10 and Cummins-powered Ram 4x2s. Harnessing 1,300 lb.-ft. of torque demanded a custom-built 12 inch dual-disc clutch system with a precision ground billet steel flywheel. The material used on the discs is an organic compound with a Kevlar weave.

With a power peak at 3,253 rpm and a tire circumference at speed of 92.75 inches, Sidewinder would have needed a 1.85:1 rear end ratio to reach 210 mph. To get that low, the Sidewinder uses a Quality Machine quick-change assembly with a 3.07 Dana 60 ring and pinion. With a quick-change spur gear set of 39-to-24 teeth, final drive came in at 1.89:1 – close enough.

The Sidewinder uses different cooling systems, depending on the purpose. For the street, a conventional radiator does fine. But for Bonneville, the Sidewinder needed a supplemental water tank housed in the bed of the truck.

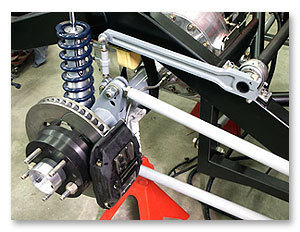

The Bonneville salt may look tabletop smooth, but it’s pocked with ridges and bumps that can create havoc (and possibly kill you) if you’ve skimped on suspension. So, as you’d guess, the stock Dakota suspension is history. The front suspension uses Chrysler screw-in balljoints, modified Stock Car Products spindles, and Speedway Engineering NASCAR – spec front hubs. An unequal-length control arm front suspension with coilover springs/shocks replaces the stock control arms, springs and shocks. At the rear, a four link suspension with Watts linkage and coil-over springs/shocks suspends the special 9-inch rear for the street, road courses, and drag racing, and the quick-change assembly for Bonneville.

The various cooling tanks, fuel cell, and batteries provide much needed ballast in the Project Sidewinder for Bonneville. Using people for ballast is not allowed. Massive Wilwood disc brakes use six-piston calipers in front and four-pistons calipers in the back. For street duty, the Sidewinder rolls on Yokohama tires – 255/45R18 in front on 18×8-inch Boyd Coddington Stingray forged-aluminum wheels and 295/45R20 in the back on 20×9 5-inch Stingrays.

The interior remains fairly stock appearing and even keeps its power windows, stereo and air conditioner. Cerullo seats are used for the street setup, and a Kirkey aluminum racing seat goes in for competitive events. The compact Vintage Air heater/air conditioning unit fits neatly behind the dash in the area previously occupied by the glovebox. A full complement of AutoMeter gauges fills the custom instrument cluster.

With the Bonneville record set, Banks is setting his Sidewinder loose on the street. Running smaller injectors, the turbodiesel will crank out 630 hp and 1,100 lb.-ft. of torque, so we’d expect to see the truck burning more than No. 2 diesel – speaking of which, it doesn’t burn much. Banks was hoping to get 20 mpg on the street. With a 3.33 rear replacing the super-low Bonneville gearing, the Sidewinder managed an average of 21.2 mpg on a 119-mile varied loop.

With the speed record comfortably in his grasp, Banks is banking on doing it again at Bonneville in August. Another record? We’d bet on it.