Banks Exhaust Brake

StreetTrucks September 2002

Bringing Your Diesel-Powered Hauler Down to a Manageable Speed with the Help of Banks Engineering

We’ve all seen those runaway truck ramps that the department of transportation has installed near the bottoms of some of the steeper grades that are part of America’s complex highway system. These ramps are built of soft gravel and as a runaway vehicle transitions off of the paved road onto one of these ramps it actually sinks into the gravel. And as the vehicle sinks, the gravel forcing itself up in front of the wheels of said runaway vehicle scrubs off speed and eventually the vehicle rolls to a safe stop. Unfortunately for the person whose bacon was just saved by the sinking of their vehicle into this soft gravel, they’re now hopelessly stuck in the gravel until they can be rescued by a tow truck. Most of the vehicles that have to use these ramps are big commercial trucks – 18-wheeled beasts that roam the earth like trains with steering wheels. But on occasion, there is a pickup truck with a large trailer and a bed full of cargo that will have overpowered its braking system and will soon find itself up to its axles in gravel.

Anybody who has ever driven a loaded down pickup over a large grade has probably suffered twofold. First, climbing the grade. With the huge load, the truck slows to a snail’s pace and after a while, you expect to be passed by either a guy on a 10-speed bicycle or a guy walking next to a burro who is heading up the grade to go collect coffee beans. But if you have been to Banks for any of their performance upgrades, you won’t have to worry about this too much. Then as you crest the grade, it dawns on you that you’re going to have to keep the truck and trailer at a speed low enough to control the vehicle until you get safely to the bottom of the hill. And while most 3/4-ton and 1-ton trucks have adequate brakes to keep from gaining unwanted speed on downhill stretches, heavy loads impose significant brake wear and the threat of overheating.

And as mechanical brakes overheat, bad things tend to happen. As the stationary brake pads are forced against the spinning brake drums and rotors, all of the components get hotter and hotter. Eventually both the stationary and rotating components reach their temperature limits, the mechanical brakes become ineffective. This is because as the rotating components can get hot enough to actually affect their structural integrity, and as the brake pads and shoes pass their temperature limits, they release a gas that gets trapped between the face of the friction material and the surface of the drum or rotor. When this happens, it is commonly referred to as brake fade. This situation is very dangerous because the friction that makes mechanical brakes work can’t happen because the trapped gasses almost act as a lubricant between the two surfaces.

While there are ways to significantly upgrade the performance of the conventional braking system, the most effective way to combat these common problems is to find an alternative way to slow the vehicle. One of the most effective ways to slow a vehicle equipped with a gasoline engine is to shift the transmission into a lower gear and use the engine to slow the truck by closing the throttle. This works because the combustion chambers are grasping for air in the intake stroke and the closed throttle is letting in very limited air and this creates backpressure in the engine. The backpressure slows the engine speed, thus slowing the speed of the truck.

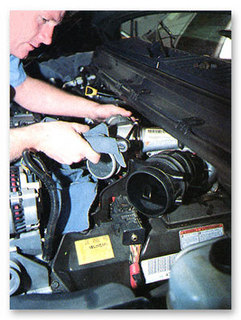

Since the Banks brake is installed on the exhaust side of the turbo, the turbo has to be removed from the truck. Once the turbo is removed, the Banks brake bolts directly to the turbo housing with the provided hardware and a drop of Loctite on each bolt. The Loctite is to ensure that the turbo doesn’t have to be pulled back out later just to tighten the bolts again.

The turbo assembly with the Banks brake attached is then reinstalled on the motor.

There is no way to physically show where the Banks brake and turbo mount, because the firewall, cowl and transmission make it impossible to shoot a photo of it. So here is a shot of how it is mounted to the display Power Stroke at Banks Engineering’s research and development facility.

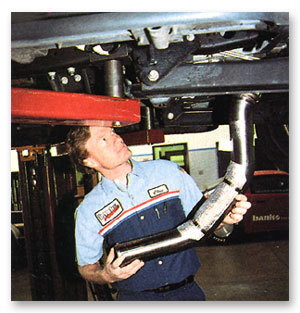

There is a new down tube for the exhaust system because it needs to be shorter than the stock unit. The Banks down pipe is also made from mandrel formed stainless steel for maximum performance. This would probably be a good time to replace the rest of the exhaust system with one of Banks 4-inch Monster Exhaust Systems – hint, hint.

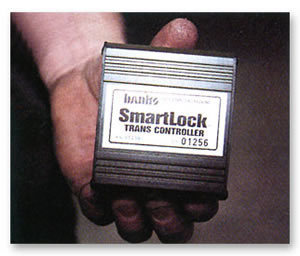

The final pieces of the puzzle are the compact SmartLock transmission controller that gets wired up and mounted under the dash and the installation of the standard 12-volt air compressor that provides the air to actuate the Banks Brake to the frame of the truck.

But owners of diesel-powered trucks have a problem because the air intake on these motors isn’t restricted like conventional gas motors are. To get any kind of engine braking power from a diesel power plant, it has to be fit with either an internal “compression brake” or an external “exhaust brake.” Both of these options are extremely effective at helping to slow the engine speed of a diesel power plant, even though the two devices couldn’t be more different.

A compression brake (or Jake Brake as it is better known) is built into the valvetrain of the engine and unfortunately can’t be added to an existing engine because it is an integral part of the engine design. It is a series of actuators that opens the exhaust valve of each cylinder at the top of the compression stroke. The engine has to then work to compress that air which is released into the truck’s exhaust system. These systems are noisy, complex and prohibitively expensive – that’s why you won’t find them in light truck applications. This type of auxiliary braking system is reserved almost exclusively for heavy trucks, busses and diesel-pusher motorhomes.

An exhaust brake, on the other hand, can easily be added to an existing diesel power plant because it is an item that is installed in the exhaust system. The reason that it is called an exhaust brake is because it uses an actuator and a shut-off valve to close off the exhaust flow to create backpressure in the cylinders and slow engine speed. This device works on the same principle as closing off the throttle on a gasoline power plant, but it is up to three times more effective and can be more closely regulated so that it reduces the chances of damaging the engine. Retrofitting an exhaust brake to a diesel-powered vehicle helps to reduce brake wear, helps keep a loaded vehicle at a safe speed on downhill grades, and they are relatively quiet. In fact, compared to a compression brake they are almost silent. In the case of the Banks Brake from Gale Banks Engineering, its design is such that it actually improves engine performance during acceleration. That’s because the Banks Brake is installed to the exhaust side of the turbo and features a cast housing for the brake that is cone-shaped. And that cone-shape is ideal for evacuating the exhaust gases from the turbo – so they have actually found a way to increase the performance of the engine during acceleration and deceleration in the same package.

To provide optimum braking, the Banks engineers have also developed an electronic accessory that goes with the exhaust brake called SmartLock. The SmartLock is a stand-alone unit that automatically locks the torque converter when the engine speed is above 1,600 rpm and also increases the transmission line pressure. This ensures that the transmission won’t slip under deceleration with the exhaust brake engaged to ensure optimum braking power.

The Banks engineers installed one of their Banks Brake kits along with the SmartLock transmission controller on a 2001 Ford F-350 dually with the turbocharged Power Stroke engine and automatic transmission and headed to one of the most notorious grades in California, the Grapevine, for some testing. But before they left, they loaded up the bed of the truck and hooked it up to a trailer to bring the Gross Combined Vehicle Weight up near the truck’s 18,000-pound capacity. They made several runs down the same 5-mile stretch of a six-percent grade to establish how the use of the different products affected the truck’s speed.

First they headed down the hill with the truck in third gear with the overdrive off and the Banks brake turned off. They crested the hill at 60 miles per hour, and without using the service brakes the truck achieved a terminal velocity of 71 miles per hour. That’s no fun with a vehicle that weighs in at just under 18,000 pounds! During the next run, they applied the service brakes halfway down the hill until the transmission could be safely downshifted into second gear, resulting in a maximum speed of 49 miles per hour after the shift. Better, but still pretty squirrelly in a truck and trailer pushing 9 tons!

Next, they crested the hill at 60 miles per hour in third gear and flipped the switch to activate the Banks Brake. Without the use of the service brakes, the Banks Brake slowed the truck to 54 miles per hour. That is a 24-percent improvement over the 71 miles per hour that they ran in the baseline test. Then they downshifted to second gear and the truck and trailer slowed to a very controllable 34 miles per hour without even having to touch the service brakes. That’s a 31-percent improvement over the 49 miles per hour that they ran in a second gear in the baseline test. A dramatic improvement, but it gets better!

The final trip down the Grapevine, they activated the Banks Brake and the SmartLock to see what they could come up with. Since they were doing the testing in a 2001 model truck that locks the torque converter in third gear, they got the same result – 54 miles per hour. But models earlier than 2001 don’t lock the converter in third and would exhibit the benefits of installing the SmartLock. In second gear the SmartLock locked the converter and the truck decelerated to 25 miles per hour. That is a 49-percent improvement over the baseline speed of 49 miles per hour, and that’s without touching the brake pedal. The SmartLock also raised the transmission line pressure by 28.9-percent and reduced the temperature at the transmission fluid by 7.6-percent proving that it has benefits aside from increasing braking power that will help prolong transmission life.

These tests help to prove that the Banks Brake is a must-have safety item for anyone with a diesel-powered pickup who hauls any kind of weight over hills of any size. And take our word for it, you don’t want to find out that you need an auxiliary brake system for your diesel-powered hauler a half-mile into a six-percent grade that is 5 miles long. Banks Engineering makes the Banks brake exhaust brake systems for Ford and Dodge diesel-powered pickups.