Banks At Bonneville

Super Rod January 2004

The dramatic story behind the creation of the Banks Sidewinder and its record-shattering run at Bonneville

Hey, you out there in Illinois, South Carolina or (heaven forbid) Texas; have you ever dreamed of going to the Bonneville Salt Flats — going really fast and setting a record? This is a good, clean, honest car guy’s dream. The dream was mine before I could legally drive. Gale Banks had the same dream, but he was in California and I was in Texas — so he got there long before I did. It wasn’t just geography, you see; from the very get-go, Banks had a plan — a very solid plan — and Buckaroo is going to use Banks as an example, so you can take a shot at your dream regardless of where you live.

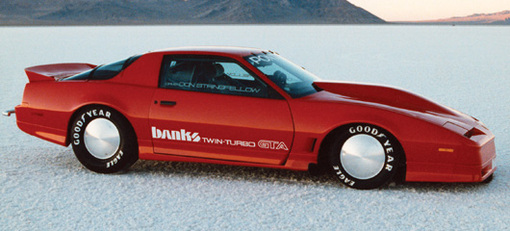

Over a 40-year career on the salt, Banks has been directly responsible for setting scores of records in dozens of classes. Some of the cars he’s been involved with have had more engine changes than tire changes. Consider the following. The Geisler Studebaker set records for 10 years in a dozen or so classes. The Sundowner Corvette coupe was the world’s fastest passenger car in 1981 at 240 mph. In 1986, Banks came back with a Pontiac Trans-Am and ran 268 mph to get the same title; a year later — with the same car — they ran 283 mph! The Teague, Welch, Banks Streamliner has gone 432 mph to become the world’s fastest piston-engine vehicle. And the list goes on.

Regardless of the vehicle he wants to take to the salt – “just because that would be fun” — Banks starts in the same place at the end of every meet. At the end of every meet? Yup. You see, win, lose, draw or break — he starts with the drive back home. Make it a long one. If you did what you set out to do — our congratulations.

Just don’t put the rig in the ditch while patting yourself on the back. Ask yourself some very cold, hard questions. Do you want to come back? And if so, why? What do you really want to accomplish, and realistically, can you do it?

What if you’ve never been to Bonneville before — even as a spectator, much less as a competitor? In that case, we could suggest you do two things. First, buy the most current rulebook available — even if it is out of date. Seriously. Also, subscribe to Bonneville Racing News. Read the friggin’ rulebook! Then read it again. Begin taking notes about items such as engine displacement and Fuel versus Gas classes. Start with any entry-level class and become comfortable with it. What do you know about the class? If you don’t understand something, read the rulebook again! Most of the time the answer will be in there, somewhere.

Let’s get back to Banks — ’cause that’s the way he does it. Almost three years before he took a diesel-powered pickup to Bonneville and set a record the first time out, Banks started by reading the rulebook. What is the existing record? How big was the engine? Start narrowing it down. Fuel? Gas? Supercharged?

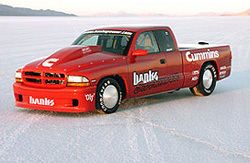

Banks knows diesels and he knows turbochargers — that’s what he does for a living. Nevertheless, for the start of a new project, Banks began with the most current rulebook. He thought an existing record of 159.657 mph was soft. In racing, soft generally refers to a record which is thought of as easy to get. Yeah, right…piece of cake.

Well, we won’t hold you hostage before giving you the outcome. The Banks Dodge truck ran 222 mph, bettering the existing record. But, take a closer look. Because Banks sells turbocharger assemblies for trucks and motor homes, he had something to prove to potential customers who don’t plan to go to Bonneville — and for darn sure don’t plan to go anywhere near 200 mph. Banks wanted to prove the reliability of turbocharged engines, similar to those found in motor homes for which he sells power-enhancing equipment, for performance, durability and fuel mileage.

His idea was to drive the truck the 700-plus miles to Bonneville while towing a double-axle enclosed trailer loaded with racing tires, wheels, tools, coolers, lawn chairs, awning, grubby clothes — and, yes, we think there was beer. The effort just to get to the salt with a street legal truck towing a 5,000-lb trailer was monumental. The truck was heavily modified — engine, transmission and rear-axle swap. This was in addition to a complete chassis revamp, including a full rollcage exceeding the specs listed in the rulebook (ah, that word again).

A fire-extinguishing system had to be thought out, fabricated and plumbed. Then there was the matter of mounting a parachute. Instruments had to be mounted and wired. And while all of this was being done — months and months of work on the truck itself — the same effort was going into the engine. The cylinder head was ported and flowed on the SuperFlow flow bench. This is extremely time-consuming work. Grinding cast iron with a handheld grinder is slow going, which makes going to the flow bench a welcome relief for the guy doing the grinding, because it doesn’t take long for his entire upper torso to start screaming for Novocaine.

A lot of time was spent designing and fabricating the 4-inch stainless steel exhaust system for the turbo (before the package went to the dyno). This package consisted of a Cummins 359cid in-line six with a 4.02-inch bore and 4.72-inch stroke. Compression ratio was 15.1:1. Peak boost was 52 psi from the Holset variable-geometry turbocharger. The fuel was No. 2 diesel. The twin air-to-water Cummins turbochargers dropped the turbo-discharge air temperature from 500 degrees F. to 100 degrees F. And finally it all came together. The engine was snugged into the truck. The systems were checked and the truck was declared “race ready” by the boss at midnight. Seven hundred miles away, the World Finals had already started. Not only did the race truck have to tow the trailer and get there; it also had to go through technical inspection and be prepped for running on the salt.

The driver was Don Alexander, who had a lot of seat time in a lot of fast cars, but never on the salt — so he had to go through the licensing procedure. He had to work up to speed, so his first pass was only 172 mph; the second run came in at 192 mph, and in short order, Alexander set an FIA and BNI record at 182 mph. Not bad for the first day on the salt! The second day, the truck set a record at 217 mph and recorded an exit speed of 222.139 mph. The on-board data acquisition was showing a massive 1,300 lb-ft of torque from the 5.9-liter turbo-diesel!

The third day was not a good day on the salt for the Dodge truck. Partway into the first pass, the pinion gear sheared in two. Alexander coasted through the clocks at 209 mph. Time to load up, go home and continue reading the rulebook.