Power Guru

Garage Magazine Issue No. 12

50 Years of Fast Times and Weird Science with Gale Banks

SoCal is a Petri dish for breeding subcultures, and in central L.A. County you’ll find holy ground for two of them. The flats surrounding Azusa were the original Mecca of drag racing, containing the legendary strips of Irwindale, San Gabriel and Pomona. Most are gone now, victims of noise ordinances and real estate values, but listen closely and you can still hear the echoes of Prudhomme’s and Garlits’ nitro cackle. A few miles to the west, Pasadena has been no less a Mecca for science dweebs. Home to Caltech and the Jet Propulsion Laboratories, Pasadena has served as Olympus to every nerd god of the last century – Schrodinger, Heisenberg, Bohr, Einstein.

Midway between, tucked in the San Gabriel foothills, there’s a sleepy little town called Monrovia. That midway point is home to Gale Banks – both literally and figuratively. Banks makes his living squeezing speed and power out of engines, employing a mental toolbox borrowed from physics and electronics, chemistry and material science.

Make no mistake, Banks is an unadulterated gearhead with a wall of Bonneville and powerboating world records to prove it. His Gale Banks Engineering operation in Azusa is a world center for diesel performance, not to mention turbocharging and even RV power and mileage. But this is not your average grease monkey; spend some time benchrodding with Banks, and in between talk of awesome hole shots and lunched blowers, you’ll hear the finer points of BTU potential and peak volumetric efficiency. That vocabulary comes from a lifetime oscillating between science and speed, two worlds where he is equally at home.

Make no mistake, Banks is an unadulterated gearhead with a wall of Bonneville and powerboating world records to prove it. His Gale Banks Engineering operation in Azusa is a world center for diesel performance, not to mention turbocharging and even RV power and mileage. But this is not your average grease monkey; spend some time benchrodding with Banks, and in between talk of awesome hole shots and lunched blowers, you’ll hear the finer points of BTU potential and peak volumetric efficiency. That vocabulary comes from a lifetime oscillating between science and speed, two worlds where he is equally at home.

That lifetime has also seen some odd, Kevin-Bacon-worthy connections. In math geekspeak, he is a strange attractor: a gravity point that accumulates chaotic orbits. For Banks they have included hot rod legends, bohemian Nobel Prize physicists, street racers, suave bandleaders, ex-Nazi civil servants, underground artists, TV stars and Mexican revolutionaries and, on one November night in Monrovia, me.

I’m at bar of the Fedora, cracking a cold one with the lanky, buzzcut Banks. The 1920-era building is the former showroom of Crunk (I kid you not) Dodge. Banks leased the joint a few years ago and converted it into a private après-wrench clubhouse. Very Sam Spade noir – art deco chairs, palms, walls covered in framed black and white photos, big hardwood bar with metalwork milled on his own CNC machines. The kind of place you would expect to find Humphrey Bogart, if Bogey was a car freak. Behind the bar, an insanely cool centerpiece Banks ‘borrowed’ as a college prank in 1962. I am under instructions not to elaborate until the statute of limitation expires.

Obviously, the speed business has been good to Gale Banks, but it began humbly enough. Banks points to a section of the wall containing family pictures.

“That’s Grandma Banks.”

The western migration of the early 20th century brought millions to SoCal, seeking fame, fortune, or escape. When Banks’ grandparents set out for Los Angeles from Des Moines, it was for a very different mission: saving souls. Grandma Banks had enlisted in the crusade of the infamous superstar evangelist Aimee Semple MacPherson, whose sprawling Angelus Temple drew crowds of 5,000 in its jazz age heyday. There, she helped Sister Aimee – whose kidnapping and unresolved death still enthralls mystery buffs – set up the first soup kitchen on LA’s sprawling Skid Row.

Banks’ father was a railroad conductor when Gale was born in 1942, just after Pearl Harbor. The elder Banks’ strategic civilian job and young family kept him from wartime military service, but he was eventually drafted in 1945 to be part of the planned invasion force of Japan. It was expected to be the bloodiest conflict of the war, but the Manhattan Project brought a quick Japanese surrender. Instead, he spent a brief postwar occupation tour in Japan working at an Army Air Corps motor pool.

“He was in charge of everything that had an engine in it, that didn’t fly,” says Banks. “My Pop was a natural wrench.”

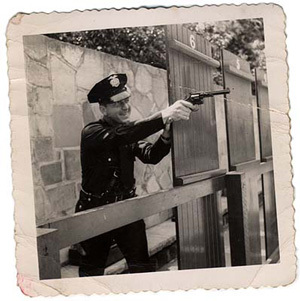

After returning, Pop Banks moved his young family to Lynwood, a new suburb sprouting in the bean fields south of LA. He stocked the new garage with machines and tools, but never wrenched professionally; instead he became a cop with the LAPD. For budding gearhead Gale Banks, Lynwood was a paradise.

After returning, Pop Banks moved his young family to Lynwood, a new suburb sprouting in the bean fields south of LA. He stocked the new garage with machines and tools, but never wrenched professionally; instead he became a cop with the LAPD. For budding gearhead Gale Banks, Lynwood was a paradise.

“My first fascination was planes,” says Banks. “I would ride down to the Compton Airport on my bike, 10 years old. I helped guys pull maintenance to get rides, and I got to ride in a lot of neat airplanes – Stearmans, Aircoupes, you name it.”

Despite his interest in flying, Banks’ attention would soon be consumed by the hotrod scene developing around his Lynwood-Southgate-Compton neighborhood. Down Atlantic Avenue, the Barris Brothers had set up shop; a little further down, Gene Winfield. Cecil Welch’s Automotive Balancing Service – the first engine balancing shop – was a couple blocks away, as was Speedomotive. Around one corner Vic Hickey was building hot heads for surplus Jeeps, creating the first off-road scene. Around another Keith Black had set up shop in his dad’s garage. All would have an impact on Banks, and at 12 he started to hotrod his mom’s $35 fixer-upper ’31 Model A cabriolet.

“I started out leaving it a flathead, because it was all I could afford,” he recalls. “I removed the stock head and had it milled to increase the compression, lightened the flywheel so much you could read through it, and shortened the shift lever down, with a big 8 ball shift knob.”

By the time he entered Lynwood High, Banks had pushed his mom’s Model A to the ragged edge, goosing the humble banger to 105 hp. Wico magneto, ’39 toploader, Winfield E carbs, Gale’s first header, Model B block, Model C crank, Jahns pistons and Durant con rods. Ed Iskenderian ground the cam and the two formed a friendship that lasts until this day. Up top, a $75 four-port Riley head. “I mowed lawns and pulled weeds for a year to get that cylinder head,” he recalls. “I did the full number on that thing.”

As an unlicensed 14 year old, the most important mod was the easy-access ignition. “Oh yeah, I hot wired it all the time,” he laughs. “It was an easy car to hotwire. My mom went out of town and I finally had a duplicate key made.”

So at 14, Banks set out street racing South Central. “I had a killer setup,” he says. “It would beat any flathead V8 pretty handily. I could beat a Chevy 6 no contest.”

The A was finally sidelined by a fragile 2-speed Ruxtell rear axle. Banks parked it and dove into’41 Chevy with a nasty 270 Jimmy lurking under the hood. He added a heavy clutch, a ‘Wayne’ plank cylinder head, and homemade 5×2 intake. Next, a ‘36 Buick sedan with a ’41 Fireball 8, sporting a 2×2 intake and Howard cam. The ungainly sedan humbled its share of competitors.

“I money raced that thing,” he grins. “One guy told me, ‘that trashbox couldn’t touch my Chevy.’ He had a 57 Bel Air with a dual quad 283, painted ‘Little Jo Jo’ on the fender. When I beat him with that Buick sedan, it just undid him. His ego was just totaled.”

It earned him respect around the Harvey’s Broiler cruise scene, and his first wrenching paychecks. Only 16, Banks set up a shop in the family garage and began doing machine work and valve jobs for neighborhood hot rod hoodlums. At the same time, though, he was honing another rep as Lynwood High’s chief pointy-head, with a nerd’s penchant for robots.

“There were plenty of sci-fi robot movies then, all were humanoid. You know, ‘gort, klaatu barada nikto.’ I wanted to build one but I didn’t think the human form was efficient; too top heavy.”

So he commandeered his sister’s chain-drive tricycle, built a plywood body, and rigged it with three military surplus servomotors. Next, a surplus radio transmitter, with a telephone dial was added to send pulse instructions. He didn’t realize it at the time, but he had created his own primitive (and wireless) programming language.

The Banks ‘bot obliterated the competition at the 1958 Lynwood science fair, and eventually second in state; in many respects it was as influential on his future course as street racing. But his interest in robotics would quickly take a back seat to Studebakers.

“My favorite car was the ‘53 Studebaker Starliner coupe,” says Banks. “The first time I ever saw one it was heaven. It was narrow and long, the perfect Bonneville car. I said to myself, I’ve just got to get one of those.”

“Anyway, Babe’s Auto Wrecking in Downey had this ‘53 Studebaker 2 door post sitting in the yard, trashed engine. Bud Lovejoy, who owned Babe’s, lived two houses down from us and he and my dad were tight. He offered it to me for $90.”

Banks hopped up the Stude’s mill, adding a Howard cam and drilling it out to 259 inches, but lunched it during a midnight race on the Corona Freeway. The search for a replacement motor brought him to the Whittier shop of George Salih, and an automotive holy grail.

“George was an Indy crew chief back then,” explains Banks.” In his shop he had a set of DOHC Indy heads in the corner, I had to know what they were.”

Those heads were the remnants of Agajanian’s 1952 Indianapolis campaign using the new Studebaker V8, with DOHC heads designed by Miller-Offy legend Leo Goosen. Only two complete engines were ever built, both of which broke. The program was abandoned and the spare parts fell into the hands of a few crew members.

“I bought the heads, front gear case and all. I forget what I paid him, $125 or $150,” he grins. “Everything needed to build a real Leo Goosen Indy engine. I set it up with two WCFB carbs for the street. I would go and bow to it; it was the coolest thing in my life.”

The DOHC motor never went in Banks’ own Stude. In August of 1958, he sold it to a friend and installed it in his ’32 Plymouth Coupe. It earned Banks $1100, a big payday in those days, and the first sale of his career.

Banks was serious about speed, but he was also serious about science. As a junior, he took a night school class at UCLA to study a new thing called ‘computer programming.’ As a senior, he built a macabre transistorized model of a nervous system.

“It had three primary neurons, an intermediate neuron, and a reaction function,” he explains. “It sensed touch and heat from a propane torch. I built an oscillator with a cone speaker. When you hit that propane torch, it screamed. If all three primaries fired, it would scream louder, by changing the amplitude.”

“Very demented,” he adds, “and very cool.”

Unfortunately, not enough to get him a repeat district prize.

“My friend Earl Ault built a linear accelerator. A freaking linear accelerator. The son of a gun! Guess who won that science fair? He kicked my tail. He was more cosmic than I was. He went on to work at Lawrence Livermore.”

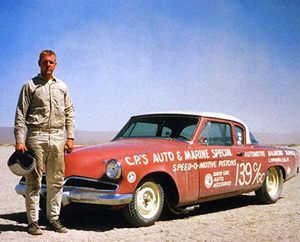

Those science fair projects caught the attention of Caltech recruiters, but his family’s modest income – and his expensive hot rod habit – left tuition out of reach. A few months out of high school, in the fall of 1960, Banks matriculated at the University of Bonneville. Two cylinders of the Studebaker’s new Chevy small block V-8 cut out (failed rocker arms), limiting his two-way average to 150.000 mph. Not bad for an 18 year old garage-builder. Not a class record, but a uniquely perfect speed at 150.000 mph.

“With two cylinders out, I argued I was really running the world’s first Chevy V6,” he laughs. The next summer would be more successful, with Banks piloting the Rochester-injected Stude up over 180.

The years between 1960 and 1967 were lean for Banks. He was attending Cal Poly, and for tuition he set up his own race engine and chassis shop (“CP Auto,” in honor of his new college) in a Lynwood alley. He came up with several innovations, including the first inboard torsion bar setups for fuel altereds. But the irregular work sometimes forced him into desperate measures.

The years between 1960 and 1967 were lean for Banks. He was attending Cal Poly, and for tuition he set up his own race engine and chassis shop (“CP Auto,” in honor of his new college) in a Lynwood alley. He came up with several innovations, including the first inboard torsion bar setups for fuel altereds. But the irregular work sometimes forced him into desperate measures.

“I was starving to death,” he says. “Somebody gave me a free case of Sego diet drink and I lived on it for a month. Man, my skin broke out. I think that stuff was radioactive.”

To pay the heat and his on-off college enrollment, he lined up a gig at L.A. city hall as a civil engineering draftsman in the traffic department, designing signal installations, and continuing his business nights and weekends.

“I worked for this unreconstructed Nazi from WWII, Ulrich Schroeder. Man, straight of ‘Dr. Strangelove.’ He absolutely never got over being a Nazi. Schroeder had this wooden leg. I’d have him walk across the intersections and time him, because I figured he was a worse case scenario for a pedestrian.”

He also worked part-time on the Union Pacific railroad as a locomotive fireman, where his foreman was Jack Stewart. Stewart was a serious hotrodder in his own right, a founder of the LA Roadsters and a legendary collector of 1932 Fords. He was also seriously into drag boats, and encouraged Banks to tap the growing marine market. “CP Auto” became “CP Auto and Marine.”

Income from the shop – and the speed equipment business Banks ran from the trunk of his Studebaker on the Cal Poly campus – was growing, which presented a problem, and another important connection.

Income from the shop – and the speed equipment business Banks ran from the trunk of his Studebaker on the Cal Poly campus – was growing, which presented a problem, and another important connection.

“I was selling a lot of stuff, but I couldn’t collect sales tax and do it all above board, so I went down to the state board to get a tax permit,” he recalls. “There was this older cat there, Don Ricardo, very dignified, kind of a Latin looking guy. Grey temples, suave. You see this guy, you think, this is a movie star.”

Not really a movie star, but one of the truly odd stories of vintage L.A. Don Ricardo was leader of the NBC Orchestra during the 1930s and 40s, and the model for Ricky Ricardo on “I Love Lucy.” He also happened to be an eccentric engineering genius who worked on the Manhattan Project in WWII, developing the first A-bomb. Ricardo was also, as fate would have it, a gearhead.

“He loved Mercedes,” says Banks. “Ricardo took a Mercedes 300 SL Gullwing to Bonneville in the 50s and ran it! He had two or three Gullwings, and a bunch of other odd stuff, Rudolph Valentino’s Hispano-Suiza, Heinrich Himmler’s staff car, all in this really rangy garage he kept building on. For some reason he had come out of retirement to work for the state of California. We shared the Bonneville experience and really hit it off. So he gave me the tax permit and waived the deposit, usually one year tax estimates. It allowed me to stay in business.”

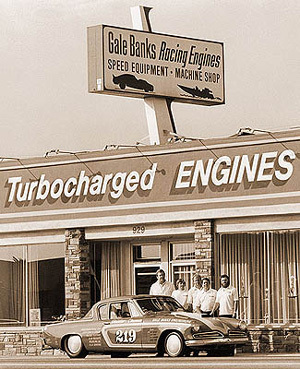

By 1967’s Summer of Love, Banks had completed his engineering education and amassed enough to move to bigger digs. In August, Gale Banks Racing Engines opened in San Gabriel. The shop serviced an eclectic mix of gearhead scenes; drag boats, quarter milers, hot VW and Corvair parts for the off-road and dune buggy markets. Another weird orbit entered.

“There was a topless bar, The Other Ball, down the street on Valley Blvd in San Gabriel,” says Banks. “A fella with Corvair van came down to San Gabriel from Pasadena for lunch everyday because he loved nude women and painted erotic art. He stops in one day because I had all kinds of Corvair stuff. Says, “I want to get some of that speed equipment.” It was Richard Feynman.”

“There was a topless bar, The Other Ball, down the street on Valley Blvd in San Gabriel,” says Banks. “A fella with Corvair van came down to San Gabriel from Pasadena for lunch everyday because he loved nude women and painted erotic art. He stops in one day because I had all kinds of Corvair stuff. Says, “I want to get some of that speed equipment.” It was Richard Feynman.”

Even by the lofty standards of late 60’s California, Feynman was an eccentric’s eccentric. A Caltech physicist, Feynman was a key member of the Manhattan Project and had just won the 1965 Nobel Prize for his work in quantum electrodynamics. He also played bongo drums, picked locks, ogled topless dancers and hopped up Corvairs.

“We started a friendship,” says Banks. “Sometimes I’d go down to the bar with him, you know, to see the topless babes.”

Sometimes they’d be joined at the Other Ball by another legend of Caltech peculiarity, artist Jerry Zorthian.

“Zorthian, this bohemian, had taught Richard how to paint,” he explains. ”He had this place up in Altadena, in a canyon. Famous parties where women would run around nude… very artsy. It was the Summer of Love thing, but he had been doing this for years.”

That relationship with Feynman may have started with Corvairs, but it escalated to Biscaynes.

“One day he drops by, with this Chevy sedan. The school wants me to help them set it up for hydrogen. It was a bugger but we did it. One day he comes by in the hydrogen Chevy, and Feynman wants to go to the local Marie Callender’s for lunch. He had these other guys with him, and I was sitting in the back with one. So I ask him, ‘what do you do?’ and he says ‘I catalog subatomic particles.’ So I say, ‘no kidding?’ so he starts explaining quarks and muons. That was Murray Gell-Mann.”

“So I’m at Marie Callender’s in San Gabriel with a carload of Nobel Prize winners, talking about hot rods over pie,” he says…“Strange times.”

Strange, but the experience sparks an ongoing fascination in alternative fuels. At the same time, the shop was a magnet for serious street racers like the legendary Big Willie Robinson. A legend on the Boulevards of East L.A., Big Willie and his wife Tomiko founded the Brotherhood of Street Racers to calm violence in the wake of the 1968 Watts riots.

“Lord, Willie was a giant dude,” recalls Banks, “6’6”, maybe 300 pounds…with a heart to match. He would drop in the shop, raising money for his new track down on Terminal Island.” That track – Brotherhood Raceway Park – became a place for South Central kids to blow off steam on the quarter mile, eventually becoming the birthplace of import racing.

Banks’ early ‘60’s city hall job also introduced him to a devastating young secretary named Vicki Lynn Johnson. They had been dating for a while when, in 1968, she lined up a John Robert Powers fashion modeling gig in New York. On the eve of her leaving, Banks gave her a counterproposal: marriage. 38 years and three kids later, he still considers it his best sales pitch.

About the same time, Banks had a technological epiphany. “There were turbos in Champ Cars, and they were starting to pop up in drag cars,” says Banks. “Ohio George Montgomery and K.S. Pittman both ran turbos. Pittman told me, ‘you can’t dream the amount of power turbos can give you.’ That lit me up.”

“We had done all the blower engines for years, for altereds and boats. The problem with blowers was they were parasites. You have to produce the power to drive the blower on the power stroke of the engine. This means more cylinder pressure and the engine wants more octane. Plus, the engine wants to spit the crankshaft out the bottom and lift the heads off the block. The new turbos ran off the exhaust stroke, which meant there’s a lot less cylinder pressure and engine stress while making the same power. I still have a parasite, but a very friendly parasite.”

Banks consulted with TRW chief engineer Hugh MacInnes, father of the Corvair turbo, and sketched out plans for a big block Chevy marine setup. In ‘69 he moved his drafting board and machines to a little industrial spot, leaving his crew to run the race engine shop, and emerged 5months later with his first Gale Banks twin-turbo marine engine.

Banks consulted with TRW chief engineer Hugh MacInnes, father of the Corvair turbo, and sketched out plans for a big block Chevy marine setup. In ‘69 he moved his drafting board and machines to a little industrial spot, leaving his crew to run the race engine shop, and emerged 5months later with his first Gale Banks twin-turbo marine engine.

“You have to be careful in a boat because if there’s a fuel leak, the air fuel mixture lies down in the bottom of the hull, and you just need kindling temperature to set it off,” says Banks. “A red hot turbocharger turbine housing will do that. I designed a new housing with a water jacket, so it was safe. I ended up selling them all over the world.”

Banks-powered boats set marks at all of the big racing venues – Marine Stadium in Long Beach, Turlock, and Oakland. They cleaned up in marathon racing, like the Parker 9-Hour in Arizona. Internationally, they won the world championship in New Zealand (which combined open sea and river racing in narrow shoals) and in Canada. But few posed a challenge like the famed Rio Balsas Marathon in Mexico.

“There was a lot of unrest in Mexico at the time,” explains Banks. “One year there were these guerillas, revolutionaries, and they started shooting at the boats during the race! Eventually the Federales came in and started firing back, and chased them off.”

Banks also made his mark at Bonneville throughout the 70’s, where he became friends with Burt Munro of “Worlds Fastest Indian” fame. Banks remembers the legendary Kiwi for his skills on and off the salt. “Man, old Burt had one hell of a patter,” he laughs. “Give him 30 seconds, and he could talk the clothes off a woman.”

Bonneville (as well as his off-road program) also acquainted Banks with Mickey Thompson – first as competitors, then friends, then neighbors. Thompson lived nearby Banks in Bradbury when he and his wife were gunned down in their driveway in 1988.

Bonneville (as well as his off-road program) also acquainted Banks with Mickey Thompson – first as competitors, then friends, then neighbors. Thompson lived nearby Banks in Bradbury when he and his wife were gunned down in their driveway in 1988.

“It was horrible, devastating,” says Banks of the Thompsons’ slaying. “Mickey told me he was worried, that it would happen.”

With the murder trial finally finished after 18 years, Banks uses guarded language, only to say that “what Mickey told me back tells me that they convicted the right guy.” He still keeps in touch with Thompson’s son Danny, and they speak of resurrecting Thompson’s last streamliner – now in Danny’s possession – for another Bonneville run.

The marine business had Banks in a groove by the early 70s, but the OPEC gas crisis of 1974 caused the bottom to fall out. “Oh, it was just hell on marine, nearly killed it,” says Banks. “People just gave up on boats.

For automotive, though, there was an opportunity. Because Banks was known as an automotive engineering house, three different car and truck magazines asked me to build economy-focused engines. So I did three packages – one each, Chevy, Dodge and Ford. The Dodge was a van, and the Chevy was a one-ton with a huge cab-over camper on it.”

Banks focused the science on efficiency, and boosted the project vehicles’ mileage up to 40%, prompting huge interest among a public still in shock over gas lines and 100% price increases. He began selling his setup as the “Banks PowerPack.” For 33 years, PowerPack has been a big commercial success, especially among RV and truck enthusiasts, both gas and diesel.

Banks’ success led to a 1975 contract to build the power train for LRSV, a government agency concept car targeted to meet proposed 1985 rules on safety, fuel efficiency and emissions. Dweebish stuff, but the science involved led to a chain reaction of bigger – and faster – projects.

“It started out as a Volvo 4 cylinder, because Volvo wanted to be in on the LRSV deal.” says Banks. “For mileage, we used extremely low mass parts, like composite carbon fiber connecting rods, and for performance, we turboed it. I really wanted this project because Volvo and Bosch had come up with the first computer-controlled, oxygen-sensing, electronic fuel-injected engine ever produced.”

Afterwards, Volvo sent several more engines to turbo and a Volvo 242 sedan to road test them. Even though he wasn’t a fan of Volvo (at the time calling them “designed by people who hate cars, for people who are afraid of cars”) but because of their then-new computerized fuel injection.

“We built the first turbocharged, EFI engine in the world in the back of a speed shop in San Gabriel, California,” says Banks. By now, Gale Banks Racing Engines had become Gale Banks Engineering.

Then Buick came calling. They were developing a turbo V6 for an Indy pace car in ‘78, and having big problems. “It was based on the old 1950s Buick V6 design, but unlike Volvo, they were using a carburetor,” says Banks. “It was down on power and running so hot you could drive at night without headlights. We helped them figure it out, and they had an Indy pace car.”

Buick returned, working with Banks to build what would become the father of the Buick Grand National – a Banks twin-turbo 437 bhp Regal. As a bonus, he got a pre-production version of GM’s new 6.2 liter diesel in 1980, and designed a home-install turbo kit for it. It was a huge success, and diesel performance kits remain the nucleus of his business.

Meanwhile, Banks was seeing major success on the Bonneville salt. In 1978, he dropped one of his twin-turbo Chevys in Bruce Geisler’s Studebaker, and the coupe smoked a two-way pass of 209. A new world record for a passenger car, but they thought it had more in it. On its subsequent run, Banks tuned it to the ragged edge. Banks and Geisler believe it was doing 230 when one of the 18” Halibrands exploded and took the quarter panel off the car.

“It damn near endo-ed,” recalls Banks. “The driver, Jack Choate, did a great job of getting the chute out and getting the Stude straight, but he never got in the car again. Scary episode, but it proved to me that my engine configuration worked.”

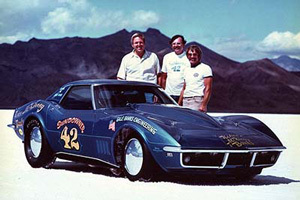

In ’80, he obliterated that record with the ‘Sundowner’ Corvette piloted by Dwayne McKinney. Banks’ 430 inch, liquid CO2-intercooled twin turbo big block pushed the ‘Vette into the 240s. This was a quantum leap for speed science when others in the class were struggling to hit 200.

In ’80, he obliterated that record with the ‘Sundowner’ Corvette piloted by Dwayne McKinney. Banks’ 430 inch, liquid CO2-intercooled twin turbo big block pushed the ‘Vette into the 240s. This was a quantum leap for speed science when others in the class were struggling to hit 200.

“I got a call one day from the chief engineer at Pontiac,” says Banks. “He says, we’ve got wind tunnel results for the new Firebird F body. If you swap out the engine from that Corvette, I’ll guarantee 20 mph more, with no other changes. So I signed the non-disclosure agreement, went on over to GM with my enclosed trailer, and picked up a camouflaged pre-production car.”

At its Bonneville debut in ‘86, it went absolutely ape.

“260 mph two way average,” said Banks. “Pontiac was happy, and they wanted to run 300 the next year, but the front tires were only good for 280. So, the next year we went back and ran a 268 two way, 283 mph out the back door [last tenth of a mile].” Remember, this car still had a tilt wheel, power windows and surround sound.

The world began beating a pathway to Banks’ door – now in Azusa – seeking street version of his 280 mph salt scorchers. “We built the first street legal supercars, with American iron, and they were world class, kick-ass cars,” says Banks with pride. “204 mph, 1.00g on the skid pad. We made the cover of Car and Driver as the first 200 mph street cars ever tested.”

Banks’ ultimate street build may have been the ‘85 Firebird for South African Peter Manillas who demanded the fastest street car on the continent. Banks tweaked and tuned its twin-turbo 427 to produce 1100 horsepower at the 6000 ft. altitude of Johannesburg. After setting the South African speed trials record at 239 mph, Manillas backed it up with a few legendary and well-witnessed 230+ mph highway laps, making it the fastest street-driven car in the world.

Banks’ ultimate street build may have been the ‘85 Firebird for South African Peter Manillas who demanded the fastest street car on the continent. Banks tweaked and tuned its twin-turbo 427 to produce 1100 horsepower at the 6000 ft. altitude of Johannesburg. After setting the South African speed trials record at 239 mph, Manillas backed it up with a few legendary and well-witnessed 230+ mph highway laps, making it the fastest street-driven car in the world.

Banks’ main business was trucks, so he made them a focus of his Bonneville efforts. Workingwith John Rock, the general manager of GMC division, Banks/GMC Syclone set a long-standing world record for pickups with a 210-mph top speed in 1990. But the biggest numbers of all came from the Teague-Welch-Banks streamliner. With Al Teague in the cockpit it pegged the SCTA chronometers at 432 mph, setting an all-time world speed record for a single piston engine.

Banks keeps on truckin’, employing all those mysterious alchemist’s arts. One customer is the military, whose boats are propelled by high performance Banks diesel marine engines. Another is Banks’ pal Jay Leno, who wanted more oomph out of the 1800-cube Continental Lycoming V12 tank engine on his infamous ‘Tank Car’ hot rod. Banks doubled the power and the mileage at the same time with his Banks-designed electronic fuel injection and a custom twin-turbo setup. Now I have enough power to get up the hill to my house” . . . only Jay Leno. Now the 9500 pound rig cheerfully blackstripes its rear bus tires at 70 mph with an estimated 1600 hp and 3000 ft-lbs of torque. Estimated, because the rear wheels spin the biggest dyno they have.

Thirty years of sporadic gas crises have made Banks an evangelist about diesel and biodiesel, which he believes is the near term alternative hot rod fuel of choice. He made that case emphatically in 2003, when he drove his diesel Dodge Dakota ‘Sidewinder’ pick-up to the salt towing its own support trailer. It uncorked a 222 mph record one-way pass, making it the new “World’s Fastest Pick-up” – and then made 24 mpg on the drive home. Today he is fielding diesel racing programs in NHRA, Baja, and road racing as he develops his vision of the future – light-weight, high-speed, smoke-free, high-efficiency automotive diesel.

And Banks continues to collect all those eccentric orbits. Every two years they converge at the Banks Gearhead Invitational at his Bradbury, California ranch. I was there for the 2006 edition, where the lawn was adorned with some of the most notable iron of the last 50 years – Mickey Thompson’s Pumpkin Seed, the Geisler Stude, Burt Munro’s Indian, the Mancillas Brothers double banger dragster, the Kirkland-Teverbaugh Bonneville ‘Vette. And you couldn’t swing a cat without hitting a hot rod legend. I took a chair to find my table companions were those two old speed lions, Ed Iskenderian and Bob Pierson.

And Banks continues to collect all those eccentric orbits. Every two years they converge at the Banks Gearhead Invitational at his Bradbury, California ranch. I was there for the 2006 edition, where the lawn was adorned with some of the most notable iron of the last 50 years – Mickey Thompson’s Pumpkin Seed, the Geisler Stude, Burt Munro’s Indian, the Mancillas Brothers double banger dragster, the Kirkland-Teverbaugh Bonneville ‘Vette. And you couldn’t swing a cat without hitting a hot rod legend. I took a chair to find my table companions were those two old speed lions, Ed Iskenderian and Bob Pierson.

“There are three honest guys in this business,” said Pierson. “One was old Vic Edelbrock. One is my pal Ed,” pointing to the cigar-chomping, Buddha-like Iskenderian. “The other one is Gale Banks.”

The last 50 years Banks has spent in the pursuit of power and mileage has provided him with plenty of legacy to reflect upon, but he is more at home talking about the future. Despite a career built on it, he is surprisingly pessimistic about internal combustion.

“Ultimately I think the Otto cycle will see the end of life as a diesel or compression-ignition engine,” he says. “I think there’s maybe two decades left. More and more we’ll be involved in new fuels technology, new electronics, and maybe even hot rodding vehicles with hydrogen fuel cells in them, or God knows what.” Towards that end, Banks has been drafted to sit on the advisory board and rules committee for the up-coming $25 million Automotive X-Prize. This prize is to be forwarded for the production of the best future high-efficiency automobile.

“We use endurance racing and speed trials to find the full capabilities and limits of the very engines and drive trains found in the trucks and motorhomes we build products for. That endurance testing knowledge, and the strength that comes from being the only engine design and manufacturing house in the aftermarket, continues our market leadership. Times and engines are changing, and we’re out front of the curve, leading it. And, we are going to stay there, no matter what the propulsive force is,” adds Banks. “There are always going to be guys who are driven to want the best. They want the power, torque, durability and mileage the factories don’t offer. We call it the ‘Banks Power option’, and it’s available for your motorhome or truck.”

“Hey, it’s not rocket science, but it’s damn close.”