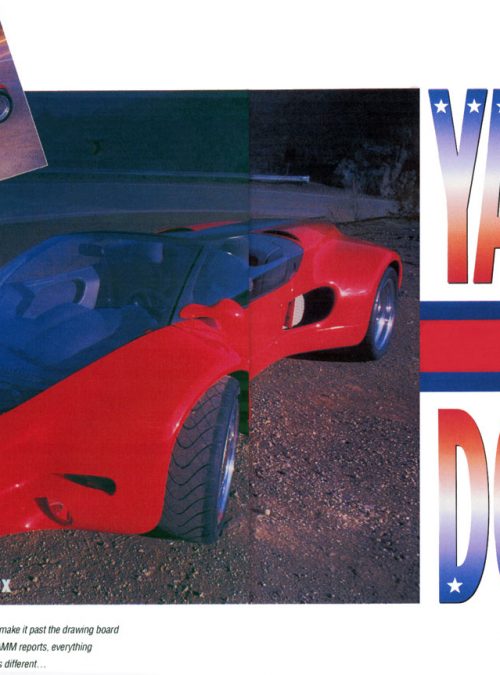

Yankee Doodle

Wheels April 1991

Automotive design studio walls are generally plastered with sketches, a wallpaper of idea drawings that are up there for inspiration, but rarely taken down and transformed into hardware. The Arex is an exception.

For its debut at the Detroit Show, officials aptly placed the mid-engined Arex beside the display of futuristic car drawings from the Center for Creative Studies, so the sports car looked remarkably like one of those sketches suddenly made real. And real is the appropriate word for a prototype that is fully functioning and ready for limited production.

‘Arex’ stands for American Roadster Experimental, and its creator is David Stollery, the one-time GM designer who founded Calty (Toyota’s California studio) and now has his own company – Industrial Design Research (IDR) – in Laguna Beach.

Stollery began his American roadster project in spring 1987 but avoided covering the wall with sketches. After only a few preliminary drawings. IDR’s Randy Robinson went to work on the scale model. Since this was to become a complete, working car, a chassis mock-up was also made combining a Lotus-like center backbone with triangulated tube structures front and rear for suspension and drivetrain.

By the summer of 1987, IDR was transferring the Arex shape to a full-scale foam core model, setting the interior package, and building a plastic tube version of the chassis. Satisfied with their direction, Stollery then fibreglassed over the foam core model to develop the car’s surfaces midway through the following year IDR had a full-size painted version of the Arex.

Then the Arex was pushed back in the queue behind IDR’s projects for outside clients like General Motors, Subaru, and Toyota. Various molds had to be made as the design was further developed and finished, but now came the part of the Arex story that makes It so unique. For a year starting In spring 1989, Stollery and crew were busy designing and fabricating the detailed work necessary to get the Arex ready for production.

Underneath Is a semi-monocoque steel tub with the center backbone and triangulated structures isolated from the epoxy-fiberglass composite body by rubber and urethane bushings. The 75-liter fuel cell fits inside the backbone and behind the seats.

The suspension front and rear are adaptations of the Toyota Supra’s, as are the brakes and half shafts. The steering rack, however, Is a custom piece built by Gordon Schroeder.

The chassis design was by Jac Brown, a Subaru engineer who had considerable experience with formula Fords, and the chassis was put together In the workshops of rally specialist Rod Millen. Brown backed up his experience with extensive computer time, checking the chassis’ stiffness and safety, and providing funds for much of the engineering work.

While the frame offers protection for the occupants, the 4 km/h bumpers normally required by US regulations are not part of the plan and don’t have to be in the limited production of some 10 per year IDR hopes to achieve. Incidentally, there Is a removable hardtop for the roadster.

The designer’s final problem was the engine. “This Is an American car,” Stollery explained, “and I feel Chevrolet has that image … the Heartbeat of America. We were unable to get GM motors, but they did introduce us to Gale Banks. Gale came down to see the car, spent about 10 minutes looking at the photos and the chassis, and said, ‘We’re in’.” What was in was a Banks twin-turbo Chevrolet 5.7-liter 436 kW V8. The gearbox for all that power? The same ZF five-speed first developed and still used for the De Tomaso Pantera.

Given that power and the Arex’s 1181 kg weight, Stollery, Banks and Brown reckon the roadster gets to 100 km/h in 3. 7 seconds and on to 320 km/h. Plans call for a second car to be finished in 1991 to serve as Brown’s engineering prototype, but what happens after that depends on how easily the money can be raised to support the project.

Getting the Arex to production would be the icing on the cake because the roadster’s first purpose was to show the automotive world what IDR can do as a design company. Given the response to the Arex, that purpose has certainly been achieved. The car makes people stop, pause, and smile. Some love it, some wonder about that long tail, others aren’t so certain, but they’re all taken by the shape and the fact that unlike so many show cars, it’s a real, producible, honest automobile. “I believe that one reason the result has been so successful,” adds Stollery, “is that right from the beginning we addressed all the problems seriously and didn’t cheat anything on the car. By cheating I mean we didn’t make the roof two inches lower for the sake of appearance even though it would interfere with the passenger’s headroom. We had the chassis resolved, we had all the mechanical componentry chosen and set in place and, to make the car look good, we didn’t reduce any of the required areas or heights of these things.”

After climbing into and out of the Arex, we can say that it does work, that the cockpit is real and usable, with a view over the short nose that IS intriguing. And it’s very easy to imagine being belted in there, the Bank’s twin-turbo whistling strongly behind you, the road rushing under you as the speedometer slips past 160 km/h and just keeps on winding to the right.