Steroids by Banks

Four Wheeler - A Primedia Publication July 1998

Dodge/Cummins 5.9L 12-valve turbo-diesel trucks

Neary undetectable once installed, the improved turbine housing that’s part of the Stinger-Plus and PowerPack® systems does its fair share of helping the packages work. Better throttle response comes naturally with this carefully designed upgrade, in addition to better flow, and hence performance.

Steroids By Banks

We used to think the Dodge Ram Cummins was a great tow vehicle—and with an extra 300 lb.-ft. of torque, it really is.

Cars behind were jockeying for position at the bottom of the grade ahead, ready to blow by the diesel pickup and sizable trailer in front of them. We’re used to seeing the first cars come by after a few hundred feet of the 8-percent grade, at about the time we needed to make the first downshift. But this time was different. The cars got smaller in the mirror, the Cummins didn’t require a downshift to conquer the grade, and, well…it wasn’t until halfway down the opposite side of the hill that those cars came zooming by, at well over the speed limit. Predictably, we caught up with them on the next uphill, wondering if any of the drivers had noticed the “Banks Power” decal on the back of the trailer. Now we wished there was one on the front bumper so those struggling econo-boxes would move over before we had to downshift because of them.

Torque is Our Friend

Bolting on extra power, and quite a bit of it, can be relatively easy when using Gale Banks’ various stages of performance parts for the Cummins diesels. The Stinger is the first level, followed by Stinger-Plus, and the complete PowerPack is the pinnacle of the Banks offerings. While there are three stages to chose from, most automotive enthusiasts (and four wheelers are usually no exception) feel that there’s no such thing as too much power. Lots of power under the hood means the ability to spin aggressive tires in deep mud, crest tall sand dunes, keep up with traffic on grades, tow heavy loads, and other good things. For those who may think that there indeed could be too much of a good thing, we should point out that there’s always a pedal, lever, or other device that can be used to regulate the power output to suit the situation. Basically, having power is nice, whether it’s needed or not.

Better exhaust flow-as much as one third-results from replacing the already decent stock pieces with a Banks Dynaflow muffler and 3.5-inch mandrel-bent Monster exhaust pipe. There was no noticeable increase in noise, just performance. On the intake side, a free-flowing air filter helps reduce restriction by some 70 percent.

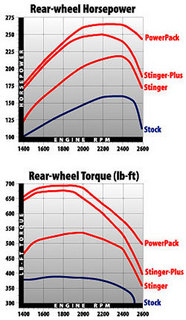

We really thought this Dodge Cummins ran pretty well before adding the Banks PowerPack®, but these graphs certainly explain why it runs a whole lot better now. However, seeing the rear wheel torque tickle 700 lb.-ft. on paper is nothing compared to actually experiencing the sensation while climbing a steep grade-especially when pulling a trailer.

A noticeable amount of the rear Dunlops was used up in dyno testing, between adding the different stages, to get the numbers for this story: Putting nearly 700 lb.-ft. of torque to the ground through four small tread patches for extended periods of time will do that to a tire. It also took several thousand pounds of ballast to keep the tires from slipping on the dyno’s rollers once the beast within the 5.9 Cummins BTA motor was properly unleased.

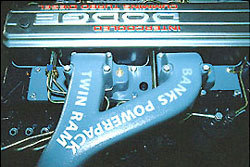

Really helping the intake tract function more evenly between cylinders is the new TwinRam manifold. A Banks-designed adapter plate takes the place of the factory single-inlet plate.

Stock Cummins intakes have two stacked heating elements. In the TwinRam manifold, the elements are installed in separate housings. Since the same amount of air flows through each one at startup as it did in stock configuration, everything works the same, minus the restriction.

A boost gauge and pyrometer are included with the upper two Banks packages, and serves to inform the driver of the engine’s well-being. Had we used a boost gauge prior to installing the PowerPack®, we’d have been able to notice that the maximum boost pressure increased by over 90 percent over stock. The dash-mounted gauges aren’t necessary to notice what that extra boost does for performance.

Power, as in an engine, really consists of two things; horsepower and torque. It’s torque that gets a vehicle going from a stop and makes it able to maintain speed uphill, and when toting heavy loads. Horsepower is more of a “go-fast” thing, good for reaching speed quickly. Having much of both is great, but for four wheelers, it’s usually the torque that counts the most. Inline-Sixes are usually good torque motors; the ’97 Lexus LX450, for example, produces 275 lb.-ft. at 3,200 rpm.

Okay, this story obviously isn’t about a Lexus, and the reason it’s mentioned is strictly to put things in perspective, as the bolt-on PowerPack upgrade described in this story produced 311 lb.-ft. of torque.

Having the torque available at low rpm is generally more desirable, and the aforementioned 311 lb.-ft. appeared at only 1,900 rpm. Quite impressive, especially considering that the latter figure is a rear-wheel measurement, complete with drivetrain losses, whereas the Lexus number is taken at the flywheel. However, the truly notable thing here is that those Banks-provided 311 lb.-ft. are in addition to the original 385 lb.-ft. of the stock Cummins motor in our test Dodge. That makes total torque put to the ground a rather stout 696 lb.-ft. No wonder those cars couldn’t keep up.

A Few Well Thought-Out Parts

There’s no magic involved with the Banks bolt-on approach to an impressive 80 percent increase in torque and a 114 percent gain in horsepower at 2,600 rpm. We know, because we witnessed the entire transformation from stock “wanna-be” numbers to the final PowerPack’d product. Carefully engineered parts is what takes the Banks-equipped Cummins to new heights—parts that Cummins likely could have designed themselves, if it wasn’t for the bean counters. Basically, a more efficient intake system, a recalibrated fuel pump cam, a better turbine housing for the turbocharger, and a more free-flowing exhaust are what woke the Dodge up. Available in three stages, the Banks upgrades start with the Stinger system, consisting of the intake and exhaust upgrades (except for the TwinRam intake manifold) and the so-called OttoMind pump calibration cam, which was good for a healthy 148 lb.-ft. and 65 horsepower. The next upgrade level is the Stinger-Plus, which also includes the Banks Quick-Turbo modification; this bumped rear-wheel output 288 lb.-ft. and 104 horsepower over stock. With the complete PowerPack comes the brand new Twin Ram intake manifold, which produced a stout 311 lb.-ft. and 127 horsepower over stock, in addition to evening out temperature differences through superior cylinder-to-cylinder distribution of the intake charge.

Win, Win and Win

One might wonder what good it does to have access to 696 lb.-ft. of torque and 264 horsepower in a pickup truck. After all, that’s pretty close to 50 percent of what 18-wheelers have to pull some 80,000 pounds with. For one thing—and we won’t even try to deny it—it made driving the Dodge a heck of a lot more fun. Just seeing the look of complete disbelief in some fellow drivers’ faces when the Cummins simply gets up and goes could be worth the price of admission. It’s also easier to drive now, as the engine doesn’t fall flat on its face when the fuel governor cuts in at 2,500 rpm. Instead, the Banks-perked Cummins now happily whirrs to over 2,700 rpm, helping make the wide gaps between the gears diminish.

More seriously, it is much safer to be able to keep up with traffic, even when hauling a load. Most people presumably buy the Cummins because it’s a capable hauler, but being able to evade those drivers who can’t quite grasp the meaning of “merge” and accelerate out of their way, can save your bacon (or whatever you’re hauling). Also, now there’s no more sitting in the right lane at 25 mph on long, steep grades, waiting to get rear-ended.

Additionally, many buy a diesel to save fuel, and as long as the extra power isn’t utilized for pure hot-rod driving, a stronger-running motor usually gets better mileage. Having to floor the accelerator isn’t exactly conducive to good fuel economy, and with the Banks PowerPack there’s seldom, if ever, a need to. A little throttle goes a long way with this kind of power under the hood, so while the want may be there, the need isn’t.

Actual Results May, and Do, Vary

Dodge Cummins engines from 1994 onward come in 160-, 175-, 180-, and 215hp versions. This one was rated at 175 at the flywheel, putting a somewhat dismal (but typical) 160 horses to the ground. The 215hp motor has better injectors, so exceeding the 264 horsepower this engine produced with the Banks PowerPack is possible. Likewise, yours may be good for more than the 311 lb.-ft. gain we saw on the test vehicle. Either way, it’s all from the simple bolt-on parts in the Banks PowerPack, which, after driving this Dodge for several months in its new state of performance, still amazes us.

| More Power to the Power Stroke Owners of 1994-97 diesel Fords can also enjoy a large performance boost with the addition of Gale Banks Engineering products. As with the Cummins, upgrades for the Power Stroke diesel are available in the Stinger, Stinger-Plus, and PowerPack levels. The rear-wheel output of the Navistar engine can reach new highs—an increase of up to 256 lb.-ft. of torque and an extra 120 horsepower. That’s a total of 616 lb.-ft. (a 64 percent increase) and 293 horsepower (a 63 percent increase). At the critical upshift point (3,300 rpm), the gains are an even more impressive 80 percent over stock. We got to test drive a PowerPack equipped ’97 F-250, and it ws truly a quantum leap over stock—which is quite a strong runner to start with. —J.N. |